Would you cosign your AI chess partner?

Takeaways

- Cosign is a new company trying to make social capital more tangible

- Whether you should do a direct listing depends on the type of company you are

- Improve decision making in a company by adopting rough, not total consensus

Question of the month

What’s an asymmetric risk you’re trying to take this year? Mine is to organise more events.

Cosign company analysis

I’ve been seeing more of Cosign recently. Cosign, still in private beta, is “an invite-only community of operators and investors dedicated to championing others in tech.”

I wasn’t cool enough to get an invite (story of my life), so I tried signing up for the waitlist. The signup process is straightforward, and assumes you have a strong twitter network. That’s a fair assumption for most people in tech [1].

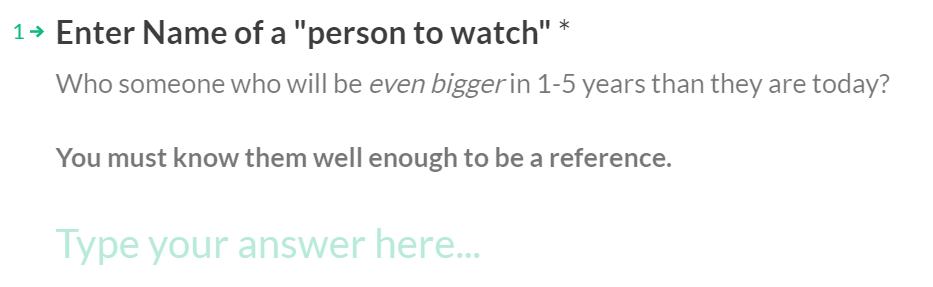

They ask you for the name and twitter handle of a person you’d like to endorse:

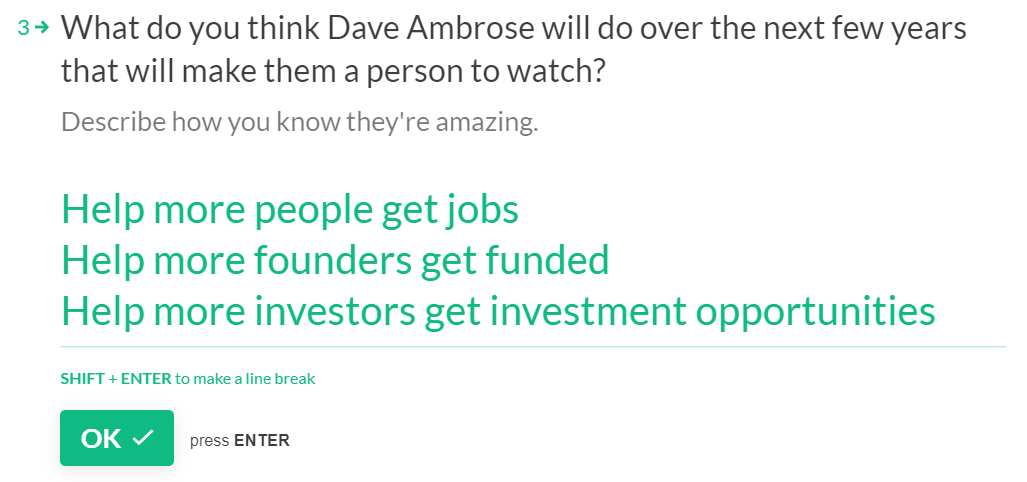

And ask for reasons:

If you’d like to move up the waitlist, Cosign also asks for the same info for a person you’d like to work with. I’m unclear what the difference is here versus the person you’d like to endorse in the first instance. Perhaps they’re testing different ways of framing of the endorsement?

My first thought is this seems like a more exclusive Linkedin. The incentive for joining is to status signal that you’re connected to fantastic people and you’re also a grateful person.

Theoretically your reputation should move in tandem with the person you’re endorsing; if they do well you look good and if they do bad you look bad. In practice you likely share more in the upside potential than the downside. If they succeed you can claim you cosigned them early on. If they fail you can claim you didn’t know them that well and were just testing out a new tech service.

Cosign continues the trend of tech making networks more transparent. From friends (facebook) to colleagues (linkedin) to hobby groups (reddit), what used to be intangible connections between people are now visible. Whereas in the past you needed a letter of introduction or seal of approval, and in the present you need an email or text, perhaps in the future all you’ll need is to check the person’s cosign page and see if anyone you trust has endorsed that person.

There are three things that I’m curious about:

- Quality checks

- Monetisation

- Ability to scale

I wonder how they check that the endorser knows the endorsee. As honoured as he would be to get my endorsement, I doubt Neil Gaiman really needs it [2] . Since it’s twitter based I assume they check if the endorsee follows the endorser? What if we know each other but don’t follow each other since our tweets are mutually irrelevant? Do they get in touch with each endorsee?

I’m also interested in the business plan. Perhaps they might run ads next to each person’s profile, though that probably makes for a bad user experience. Maybe they could do a freemium option like Tinder or Lunchclub. A paid subscription could surface your profile to others and offer an opportunity to connect, you could get more endorsements compared to the free version, or you could get forwarded interesting opportunities.

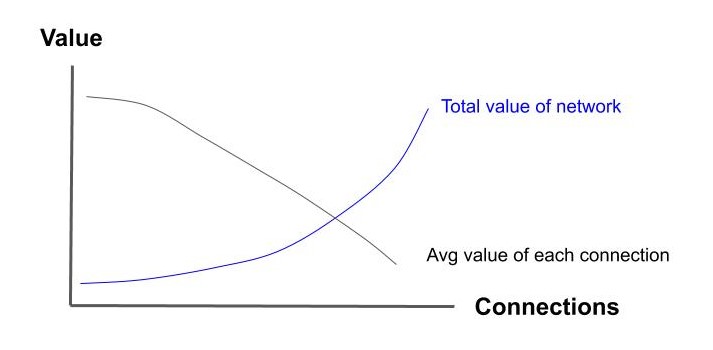

I’m most curious about how they will overcome the problem of scale. As with most social networks, Cosign should be more useful the more people are on it. The more people on it, the higher the chance there will be an endorser you know, which is better signal. All things equal, I’d rather have 100 endorsements of how awesome I am compared to 5.

Of course, things are never equal in real life. All of us have Facebook or Linkedin connections that we don’t need. It’ll be a struggle to keep endorsements meaningful and scarce as they grow the community.

Overall, I’m interested in tracking their progress over time. Maybe they end up limiting the group size, and doing what Column is trying to do with exclusive networks [3]. Maybe they pivot into recruiting. It’s too early to tell, though I’d Cosign Cosign.

IPOs vs direct listings

Aswath Damodaran, one of the best finance profs out there [4], wrote about IPOs vs direct listings a while ago. I’ll review highlights below; banking ex-colleagues feel free to disagree. If you aren’t familiar with direct listings, a16z has a primer.

but the biggest difference [in direct listings] is that it cannot raise fresh capital on the offering date […] That is not as much of a problem as it sounds, since the company can choose to raise cash in a pre-listing round from interested investors, or to make a secondary offering, in the months after

The inability to raise new capital remains true for now, after the SEC rejected a proposal to allow it. As Aswath points out, this isn’t a dealbreaker since companies can raise before or after the listing instead.

Aswath describes the case for and against banks managing an IPO vs listing directly with less bank involvement [5]:

Timing: Banks argue their experience and relationships give them insight on the best time to IPO

Damodaran argues that no one can really time the market, as seen when momentum abruptly shifts, such as in late 2019

I lean more towards Damodaran’s side here. In the bank’s defense, in their role as middlemen talking to investors, they do get regular feedback on how investors are feeling. You can’t say for certain until you try to actually price your stock though.

Prospectus expertise: Banks argue their experience can help guide the drafting of the filing documents

Damodaran argues that most prospectuses look similar, particularly the risk and business sections.

I agree with Damodaran, though as he implied most of this is due to legal reasons. Risk sections in prospectuses are more for legal protection and less for telling you what’s important [6]. I know ex-colleagues that spent a lot of time drafting sections for the company, but it’s hard to add significant value here (sorry guys), especially if the company going public is full of ex-bankers as well.

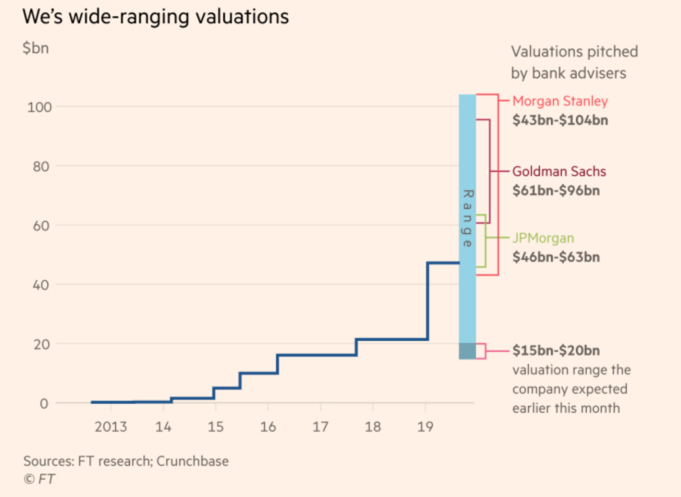

Pricing of the IPO: Banks argue they can help bridge the gap between the last private round and the intended public price, find the right comparable company set, choose the appropriate valuation multiples, and identify investor concerns.

Damodaran argues that banks do a bad job at pricing, as seen in the WeWork IPO. This is because they’re choosing the wrong comps or multiples, talking to the wrong investors, or biased in the pricing process, with the last being most likely.

Choosing the wrong comparable company set or multiple is less of a factor. The comp set is socialised among investors beforehand so there’s usually broad agreement there [7]. There’s only a handful of common multiples (EV/Rev, EV/EBITDA, P/E) so the type of multiple is also broadly understood.

I agree that banks are biased in the pricing process though, and they are incentivised to be. As Matt Levine has written before, the bank is pitching to get hired by the company, hence the higher the price range pitched the better. It’s easier to get hired when you tell the CEO he’s worth $1bn instead of $100mm. When they do get hired and need to meet that price is when they start managing expectations.

The right price for the company is a difficult question, and we’ll come back to that later.

Marketing: Banks argue that they can reach out to their investor clientele and expand the investor base for an issuing company

Damodaran argues that a) some companies are now better known than the banks themselves, and b) investors are more skeptical of bank pitches now

The first is subjective; Slack and Spotify can market themselves, SiTime likely can’t. If you’re less well-known, having a bank to market you is probably a good idea. The banks will have connections with investors, you won’t.

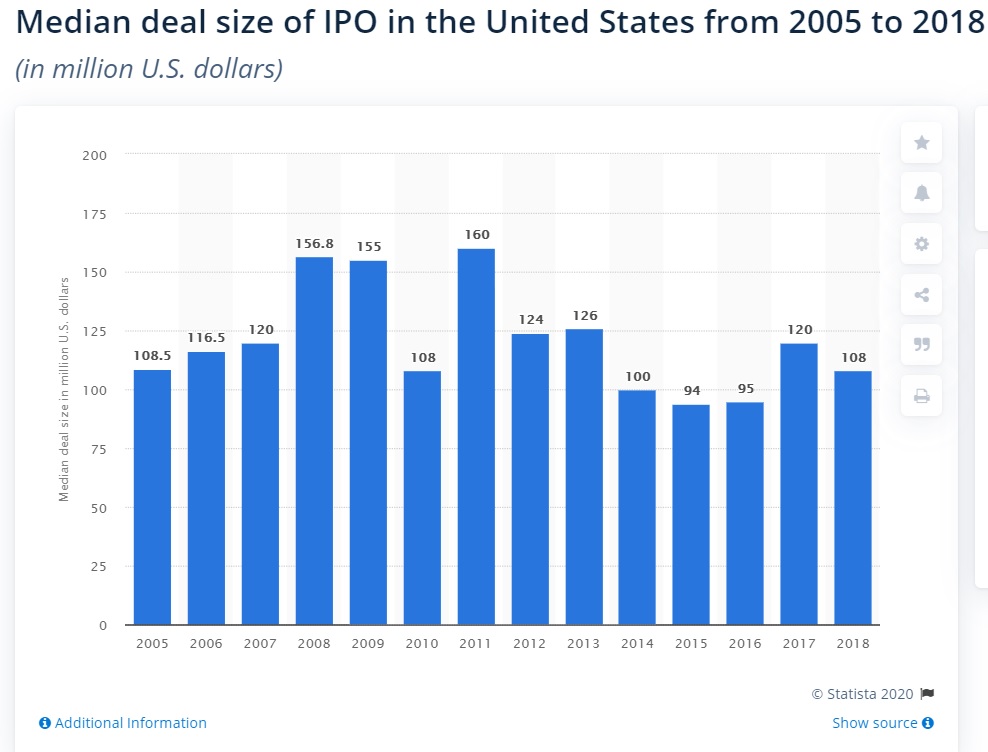

Keeping in mind that the median IPO offering size is ~$100mm, and that IPOs sell ~20% of the company, we can infer that most IPOs are not the large household names you’re already aware of. You can browse the list of recent IPOs and see how many you recognise. Most companies probably benefit from having a bank market them and reach out to investors.

The second point seems irrelevant. If you’re a professional investor (buyside) you’re not making a decision based on equity research (sellside) recommendations anyway (sorry sellside friends). If you’re a retail investor you don’t get that info.

Underwriting guarantee: Banks argue they can accept pricing risk and guarantee your stock gets sold at a price

Damodaran argues that if IPOs are underpricing companies anyway, guaranteeing a lower price isn’t helpful

Underwriting guarantees were more relevant historically and are less relevant now. We’ll come back to the pricing issue.

After-market pricing support: Banks argue they can help stabilise the price right after the stock starts trading

Damodaran argues this is difficult to impossible for larger company IPOs

Agree that price stabilisation is hard in large IPOs. Given the context above of the median IPO offering size though, I think this still has value for many companies. The way that banks price stabilise is by selling more stock than allocated and entering into a short position against the company. The bank either gets shares from the company or the open market to cover the short position, hence supporting the price before the open [8].

What is the right price? This is a complicated question. A common feature of IPOs is that stock will be pre-sold to professional investors at one price, say $10, and then start trading on the open market post IPO at a premium, say $20. This IPO pop has been criticised by VCs such as Bill Gurley, who say this inefficiency is a money transfer from private investors (VCs like Bill) to public investors who got shares during the IPO process [25].

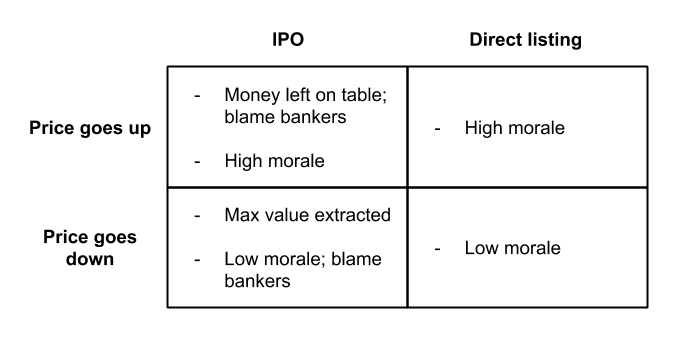

I agree there is inefficiency in pricing, but most companies prefer underpricing resulting in the stock trading up, rather than overpricing and the stock trading down. If we blame bankers for underpricing, we should applaud them for overpricing and getting the most amount of money for the company. I don’t see anyone doing that, understandably.

Companies seem willing to trade off the inefficiency for better morale. Sure, you could have gotten $20 at the open and then have the stock trade flat, but the pop from $10 to $20 does (irrationally) make people happier. Also, what if you open at $20 and trade down to $10 three months later? What was the right price then?

Damodaran concludes by giving reasons why the IPO status quo has held, citing inertia, fear of harming the banking relationship, and companies needing someone to blame. I agree with these. In the end it depends on your company; a direct listing does have more price efficiency by definition. If you’re large and well known, you likely can direct list and shouldn’t be taking advice from an email newsletter anyway. If you’re small and not, you probably need bankers to help market and connect you with investors. I’m 80% confident IPOs will still be majority of listings in three years time.

What is rough consensus and how can it improve decision making efficiency

Decision making becomes more difficult as your organisation grows. You want to involve everyone and make them feel included, but that could spiral into multiple meetings where people give input but nothing gets done. This summary of IETF decision making principles by Devon Zuegel [30] has advice I haven’t seen before:

We reject: kings, presidents and voting.

We believe in: rough consensus and running code.

The part about rejecting individual decision makers and voting is straightforward. Running code can be thought of as getting things done; preferring action over theory. More interestingly, what does rough consensus mean?

If […] the working group has made an informed decision that the objection has been answered or is not enough of a technical problem to prevent moving forward, […] there is rough consensus to go forward, the objection notwithstanding

The key insight here is that objections that are “not enough of a problem” can be overruled. This implies to go ahead with decisions that some people in the group dislike, as long as the issue isn’t critical to success or failure. You don’t need everyone to agree the decision is optimal.

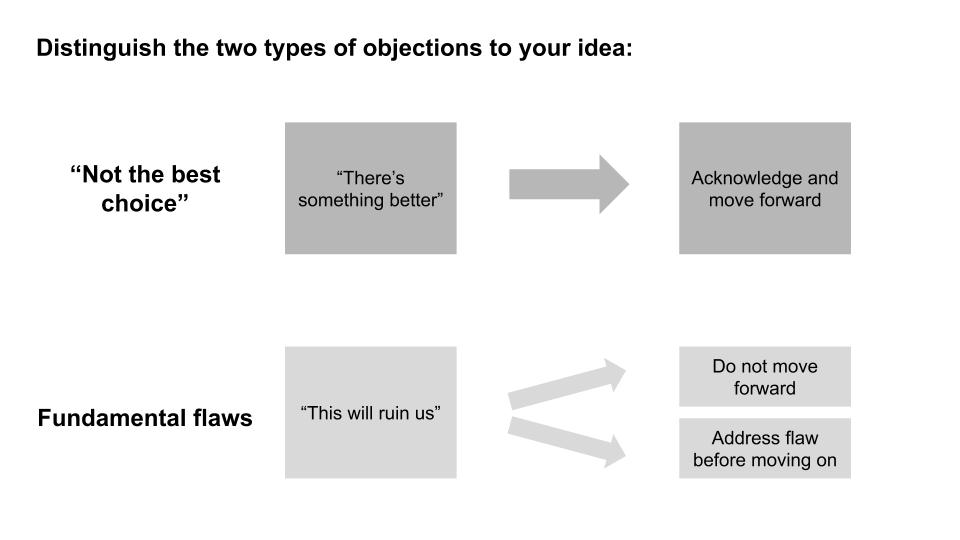

Rough consensus relies on the distinction between two types of objections:

1) “Not the best choice” feedback: “I don’t believe Solution A is the best choice, because XYZ. I believe Solution B would be better, but I accept that Solution A can work too.”

2) Fundamental flaws: “I believe Solution A is unacceptable because XYZ.”

During a discussion, clarify which type of objection you’re getting, since people communicate with various degrees of subtlety [31]. My “unsure about this” is usually a “pretty sure this is wrong” . Once clarified, spend the majority of your time discussing fundamental flaws rather than “not the best choice” feedback.

How you define a fundamental flaw depends on your team, and should be decided beforehand, another difficult task in itself. Devon cites substantial technical debt, inability to scale, or too much work as some suitable reasons. You probably can’t have too many reasons, as that would lead to nothing getting done. Once you’ve settled on your reasons, there should be a high bar to accepting new ones during the discussion itself.

People are incentivised to participate during meetings; I’d also assume that most people talk during meetings for the sake of talking [32]. This implies that most objections should fall under the “not the best choice” category, and you should feel alright moving forward in the majority of cases.

A chair who asks, “Is everyone OK with choice A?” is going to get objections. But a chair who asks, “Can anyone not live with choice A?” is more likely to only hear from folks who think that choice A is impossible to engineer given some constraints

I like the reframing of the question, and intend to use it more.

Some things that seem like consensus actually are not:

An engineering solution that has no objections, but also has no base of support and is met with complete apathy, is not a solution that has any useful sort of consensus

conceding when there is a real outstanding technical objection is not coming to consensus

Even worse is the “horse-trading” sort of compromise: “[…] Neither of us agree. If you stop objecting to my proposal, I’ll stop objecting to your proposal and we’ll put them both in.”

All these are related to people giving up on caring about the issue. This is problematic, and unfortunately I’m unsure of the best way to revive the interest of the group. Perhaps taking a break and coming back another week?

One hundred people for and five people against might not be rough consensus

Five people for and one hundred people against might still be rough consensus

The original document gives more detailed examples of the above points [33], with the main takeaway coming back to whether the objection is a fundamental flaw or not. The number of people for or against does not matter.

We may use the “hell yeah” principle for hiring and some other decisions, but we use the quick iteration principle when we ship things. We don’t aim for perfection the first time — we build fast, we ship, we learn, we iterate, and we ship again

I agree. As can be inferred from my writing, I’m biased towards experimenting. You don’t know what you don’t know, and you can’t find out until you try. There’s too many slide decks and too much theorising compared to people actually executing, since the former is easier to do and still feels productive, whereas the latter is harder and uncomfortable. Unless the flaw is going to ruin your business - and few do - err on the side of getting things done [34].

I like the idea of rough consensus because I care about very little prefer efficient meetings. Since most organisations incentivise people to speak up, you usually end up with more opinions and objections than needed. While adopting a rough consensus approach seems against the principle of inclusivity, it likely increases effectiveness in decision making.

Shoutouts

- Thomas Guthrie at onejob is helping people find their next roles at top startups.

- A friend in equity research is looking for a junior person that wants to cover healthcare tech, lmk if you’re interested.

Other

- Could a text prediction algorithm (like gmail or your phone keyboard) be used to play chess?

- Self-disclosing weakness at work could help or hinder, depending on your status. See here for a tweet summary

- Examples of games made by China tech companies for Chinese new year

- How some restaurants PR their way to success and best-of lists

- How to design complex and aesthetically pleasing mazes

Footnotes

- I have a strong irrational dislike of twitter but begrudgingly acknowledge it can be high value add

- If you’re actually Neil Gaiman and want my endorsement, we should chat. In person. I might bring one or two books to get signed.

- I came across the Column business plan too late to write about it for this month, and you can find out more about it here

- Not just in finance but in actually wanting to educate too. How many profs would tell you to get their book for free online instead of paying for it?

- Full disclosure, I used to be a coverage IB analyst, and worked on IPOs. Also, investment banking has nothing to do with investing, in case you weren’t already aware.

- Companies are incentivised to throw every possible risk they can into the prospectus to reduce legal liability. This is why you see statements like “we have never made a profit and may never make a profit”

- It goes something like this: Investor will ask bank “Hey what comps are you thinking of”, the bank will say “This set, this other group, and also this bunch”, the investor will say “Oh hmm that’s interesting you included that group too but otherwise looks right. What are other investors thinking?”, the bank will say “Oh they’re comping it against so and so too”

- This is known as a greenshoe option, after the first company that featured it

- You can see why Bill might be biased here

- Forwarded by Eitan on twitter. The original IETF document can be found here

- This also applies to feedback generally, as I summarise here about how to get better at taking feedback

- To be clear, I’m agreeing that you should speak up at work as much as possible; I just dislike the fact it’s necessary

- “So, in a large working group with over 100 active participants and broad agreement to go forward with a particular protocol, if a few participants say, “This protocol is going to cause congestion on the network, and it has no mechanism to back off when congestion occurs; we object to going forward without such a mechanism in place”, and the objection is met with silence on the mailing list, there is no consensus. Even if the working group chair makes a working group “last call” on the document, and 100 people actively reply and say, “This document is ready to go forward”, if the open issue hasn’t been addressed, there’s still no consensus, not even rough consensus. It’s the existence of the unaddressed open issue, not the number of people, which is determinative in judging consensus.””

- Eitan points out this leads to a similar effect of “disagree and commit” that Amazon supposedly has

If you liked this, you’ll like my monthly newsletter. Sign up here: