Doctor GPT-3 or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Artificial Intelligence

Takeaway

GPT-3 is an impressive model of text prediction that generalises to many use cases. I walk through how it works at a high level, whether the hype is deserved, how to detect GPT, and whether it’s going to plunder our jobs.

Only human after all

About a week ago, Sharif Shameem shared this video on twitter demonstrating the abilities of a new AI, GPT-3:

This is mind blowing.

— Sharif Shameem (@sharifshameem) July 13, 2020

With GPT-3, I built a layout generator where you just describe any layout you want, and it generates the JSX code for you.

W H A T pic.twitter.com/w8JkrZO4lk

And. Twitter. Freaked. Out.

Perhaps realising that their cushy jobs of copying stack overflow answers or gossiping about startups were at risk [1], programmers and VCs alike on twitter started flooding the feed with GPT-3 demos and hot takes on this newest artificial intelligence. They’re still going on, if you want to take a look

So, here I am, with my own hot take, to cash in on all that captivated audience for AI.

Hey man, I’m only human.

The article is split into 5 sections:

- Explanation of what GPT-3 can do, why it’s impressive, and why people are concerned

- Slightly technical overview of how language models worked before GPT-3

- Slightly technical overview of how GPT-3 works

- How to detect text written by GPT-3

- Implications of GPT-3

Let’s get started.

1. GPT-3 is impressive because it can create intelligible outputs for a wide variety of use cases

GPT-3 was created by OpenAI, a company trying to “make sure artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity,” i.e. the robots don’t kill us all.

GPT-3 is a general language model, meaning it takes some words as input, and produces more words as output. Think of it as an amazing autocomplete function. Because it’s a general model, it can solve many different types of tasks. You could ask it to write a paragraph about unicorns, translate a sentence, generate programming code, or more.

This is nifty since you’d normally expect an algorithm to only do what it was trained for. You don’t type into excel and look for it to tell you a poem. For a long time now, we’ve expected programs to do as they’ve been told, with poor ability to do tasks they were not designed for.

Since it’s a general model, you’d also think GPT-3 would be worse at a task than models specialised for that task e.g. when comparing GPT’s translation results vs an algorithm only focused on doing translation, GPT won’t be as good.

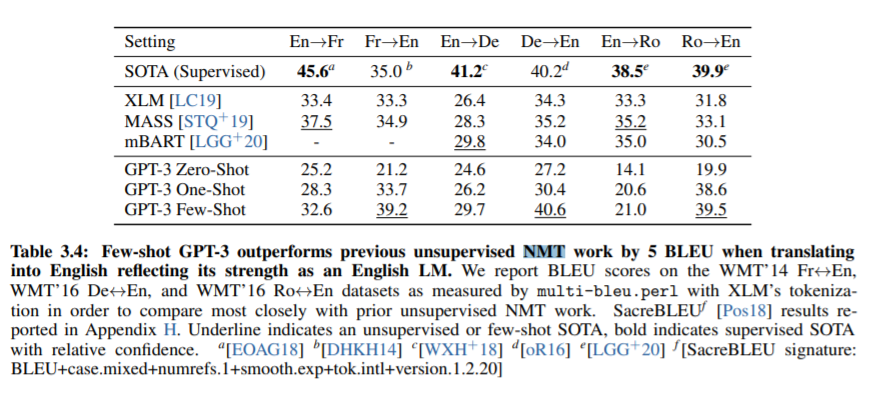

Surprisingly and impressively, that’s not always the case. Below is the table from the GPT paper with the results of a translation test. For simplicity, we can just compare the first line representing a “State Of The Art” model against the last line representing the best performing GPT model [2]. A higher number is better here. We can see that for some of the translation tasks (particularly for translation to english), GPT is as good, if not better than State Of The Art models.

OpenAI tested GPT on a large variety of other tasks, such as text prediction, trivia questions without letting it search a separate dataset, or determining what word a pronoun is referring to [3]. While GPT doesn’t win on all cases, it gets great results in most of them. If you could only pick one model, you’d probably want to use GPT. It’s the Simone Biles of the AI community, being top at many events and great at the rest.

Let’s take a look at some examples.

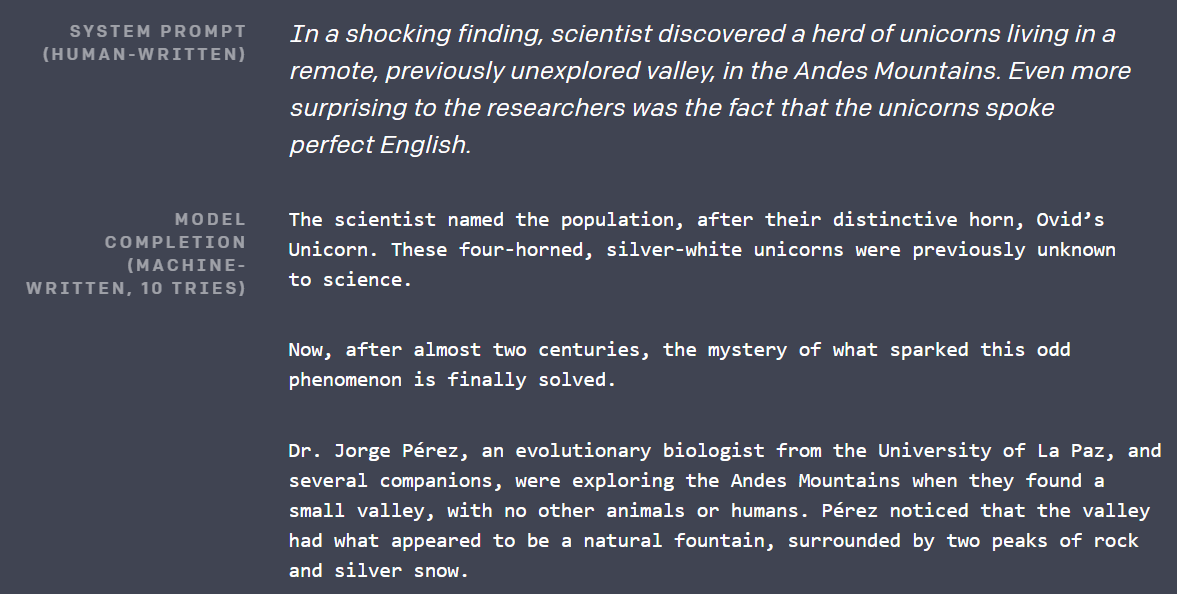

In this first image below, the model is fed a prompt at the top, and then comes up with the remainder of the text below. The text goes on for longer; I just cut it off for display purposes. Pretty awesome what it came up with right?

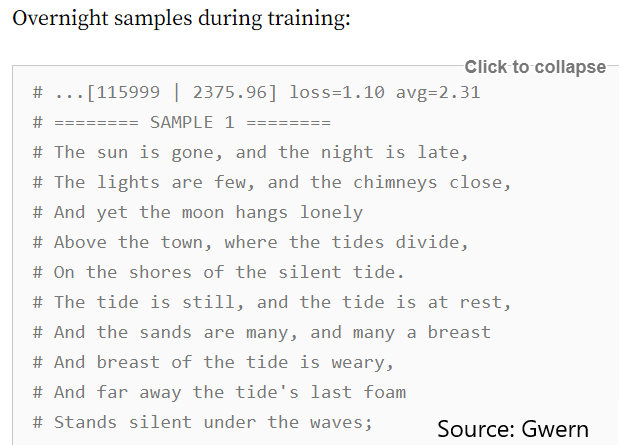

In this second image, we see another sample text generated from the model, this time showing that it can produce poetry as well. It’s probably better than what I’d write myself.

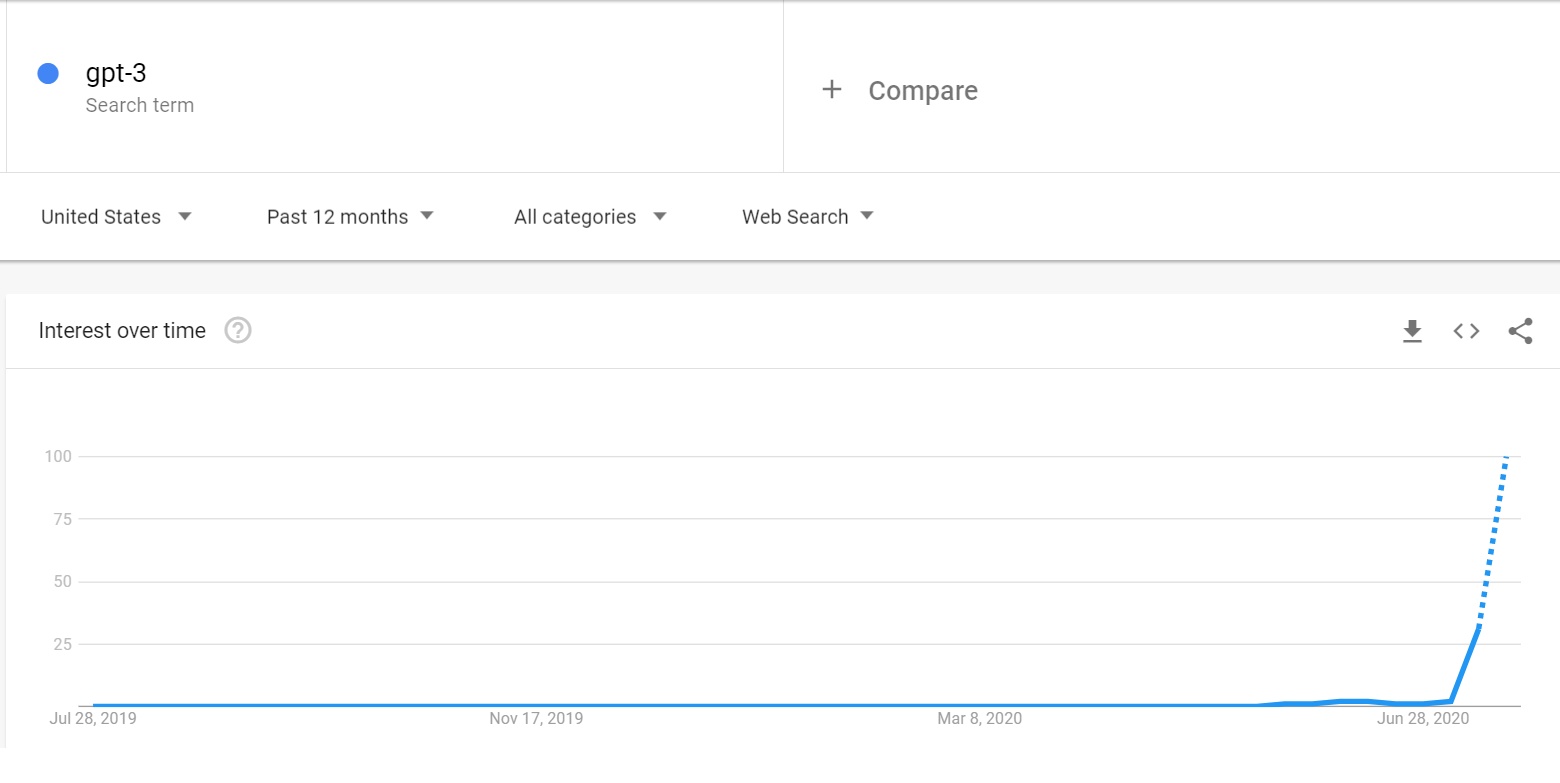

Amazing, so all the hype’s justified then? Was this some watershed moment, when the ability of AI crossed some artificial boundary? Twitter and Google trends certainly seem to think so.

Well… yes and no.

Those two images I just showed? I lied, those aren’t from GPT-3.

They’re actually from GPT-2, the older model released in February of 2019. In fact, long time readers of this newsletter might recall this article I wrote back then, highlighting the already admirable results from the model [4]. The text generated from the older model was already awesome.

So, what’s different this time? Did the robots just get a better marketing department?

Partially, yeah. GPT-3 was released at the end of May. If you scroll back to that Google search trend and squint really hard, you’ll notice that itsy-bitsy bump in the graph, two weeks before it really starts spiking. That was the public interest in GPT-3 before the viral tweet. Goes to show that presentation formats can really make a difference and I should quit writing to make Tik Tok videos.

That said though, there are actually impressive improvements this time round as well. GPT-3 gives better results than GPT-2, and can generalise to more scenarios. This is largely due to the increased data used in training and increased model parameters.

I’ll elaborate more below, and the way these models work are that they take in data, train on them, and change their model weights according to the training set.

It’s been known for a while that more training data usually helps [5], and the results from GPT-3 continue to show that it’s true. GPT-3 ingested ~50x the amount of data that the older version did, giving some intuition on how it can come up with so many relevant references for its outputs [6].

GPT-3 also has ~100x the amount of parameters in its model compared to the older version. Having 175bn parameters isn’t unheard of, but it does help GPT-3 get even more differentiation in its replies [7].

Max Woolf points out two other things that are improved in GPT-3: 1) It allows for text generation twice as long, and 2) prompts to the model are even more helpful in steering the direction of text generated. GPT-3 can take zero, one, or a few “prompts” of sample answers when you’re giving it input. The prompts help guide its understanding of what answers to give, and the more prompts the better.

Overall, Max estimates that GPT-3 gave him usable results about 5x more often than the older GPT-2. In terms of hype, the general public has gone from 0 to 100, whereas people watching the space have gone from 50 to 70.

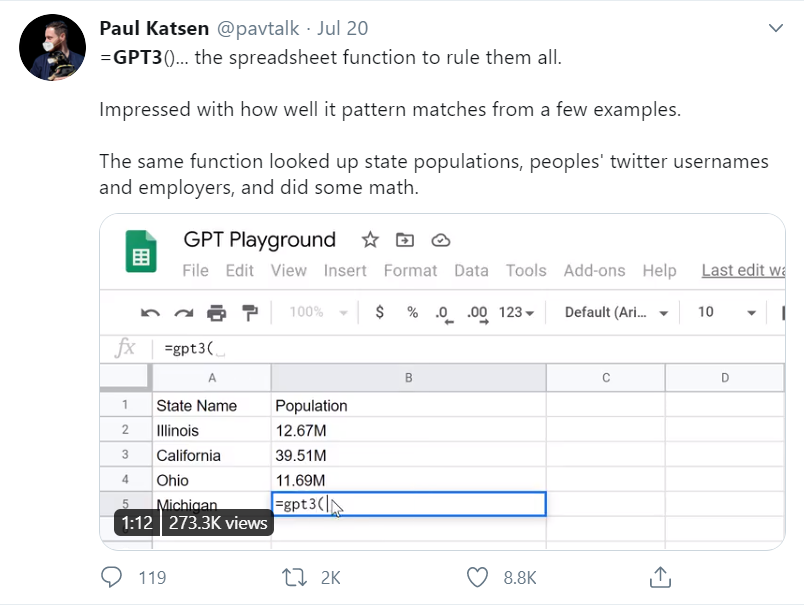

This allows for results such as this, a plugin to pull GPT results to autofill google sheets (real demo this time, I promise):

Since GPT generalises well, there’s a lot of excitement around it being used in any “knowledge work” field. From programming to banking to medicine, there’s thoughts that GPT can eventually give answers of the same quality a professional would. The next time you visit a doctor, maybe your diagnosis will come from Dr. GPT.

That all sounds great, what are the concerns?

Max goes into more detail here, pointing out that:

- The model is slow on producing output

- There’s been a lot of cherry-picking in the examples shown publicly

- Everyone’s working with the same trained model and we can’t finetune it

- There’s an ongoing issue with systematic bias in the training e.g. recall how Microsoft had to pull its chatbot after it turned racist

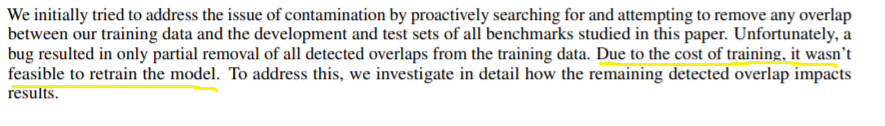

Another concern is the cost of training such a model. Amusingly enough, Yannic on youtube pointed out that the researchers made a mistake in some of the data collection, and didn’t realise it until they had already trained the model. Rather than start over, they had to adjust for that problem in other ways, since it was too expensive to retrain the model.

That’s wild. People are hoping that model training costs come down, as hardware catches up to the algorithm requirements. If they don’t, it’ll mean that only large companies will be able to customise models for their own purposes.

Lastly, there’s also the unending unease about how this will wipe out all our jobs and bring about the end of humanity. I’ll touch on this light subject in my concluding remarks.

Now, let’s take a closer look at how the models work.

2. Overview of the seq2seq model used before GPT-3

Disclaimer: The next two sections get slightly technical as I explain the models used. Feel free to skip over to the “How can we detect GPT-3?” section after if not feeling up to the challenge.

Further disclaimer: I’m not an ML expert, and the models involved are complicated. I’ll be leaning on this talk plus the other explanations linked at the bottom of this article. Feel free to reply with any corrections.

GPT-3 uses a different model compared to traditional prediction models. However, it’s still helpful to get the intuition behind the older models before looking at GPT-3. I’ll first walk through an old model, and then walk through GPT-3.

We’ll start with the popular, older sequence to sequence model. This is commonly abbreviated as “seq2seq”, but to make things even easier to understand, I’ll just refer to it as “old model”, and GPT-3 as “new model.”

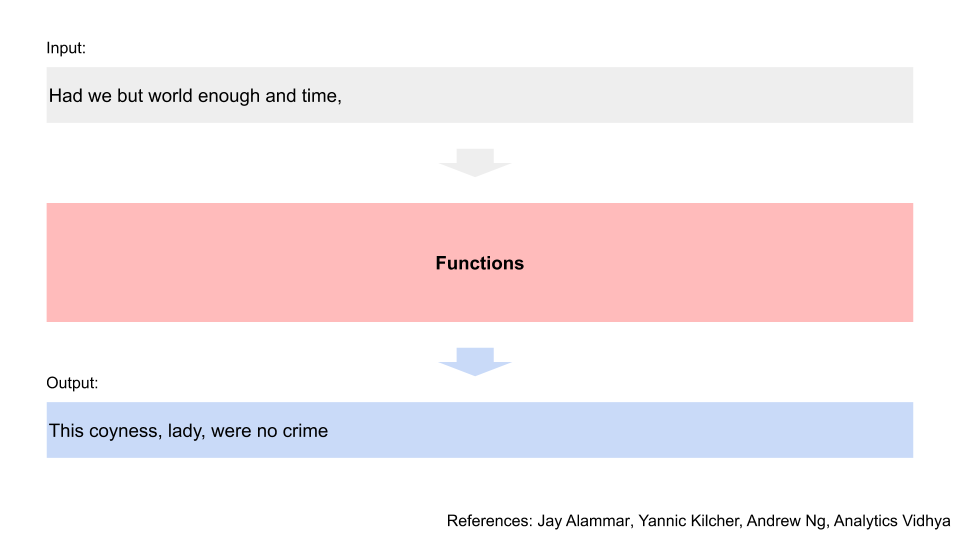

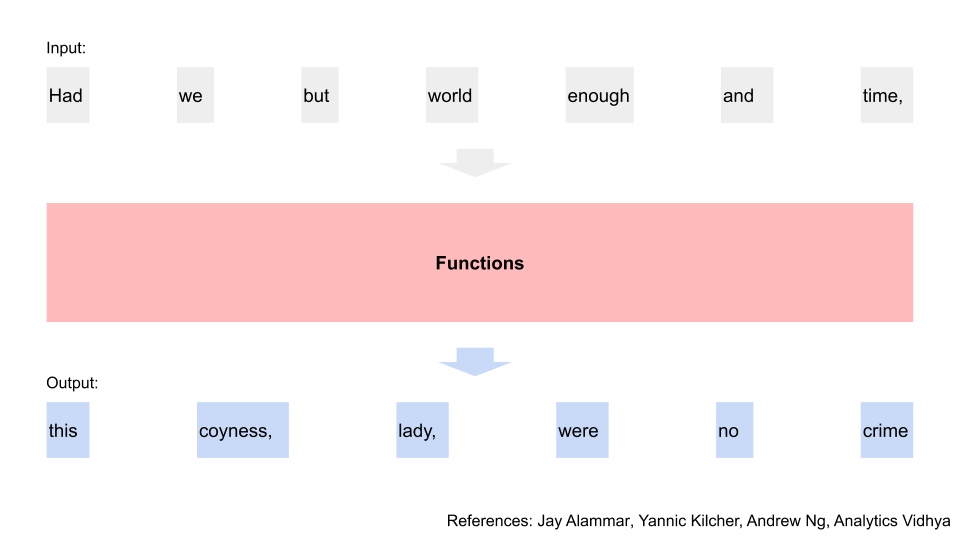

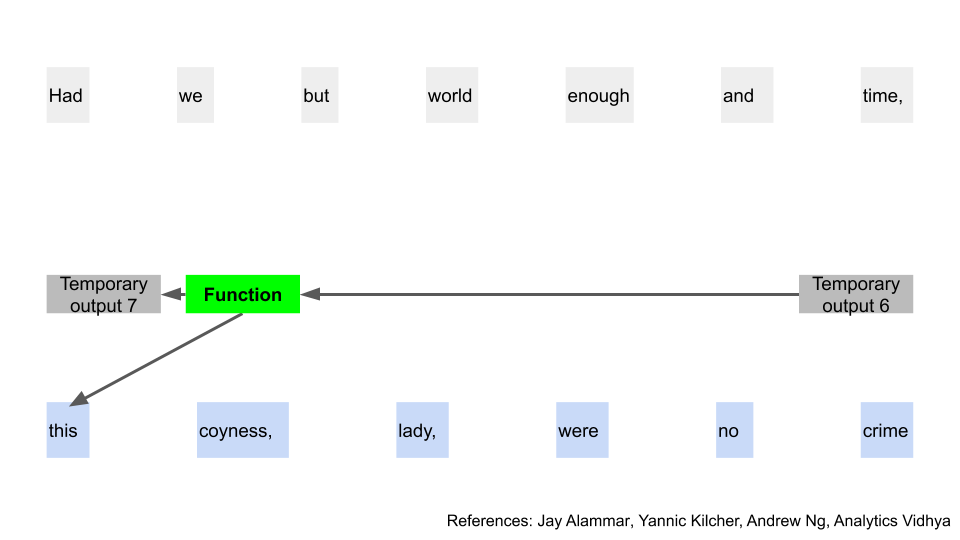

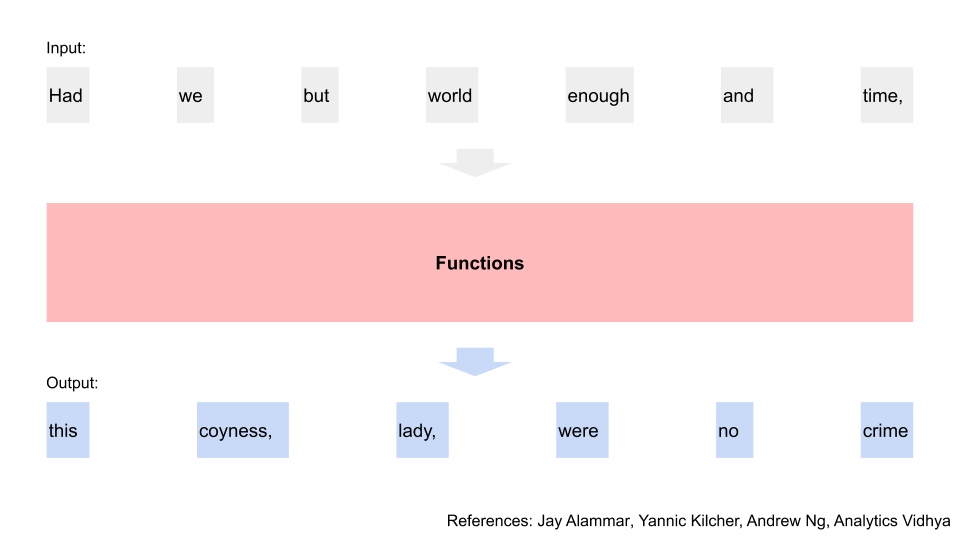

Suppose we had a phrase, and wanted to predict the next phrase. We’d put our phrase through our algorithm, which is a series of functions, and then get the predicted output.

Every word matters, so we have to split up the input phrase and look at it one word at a time. e.g. “Had we but world enough and time” has different connotations vs “Had we but world enough and limes”

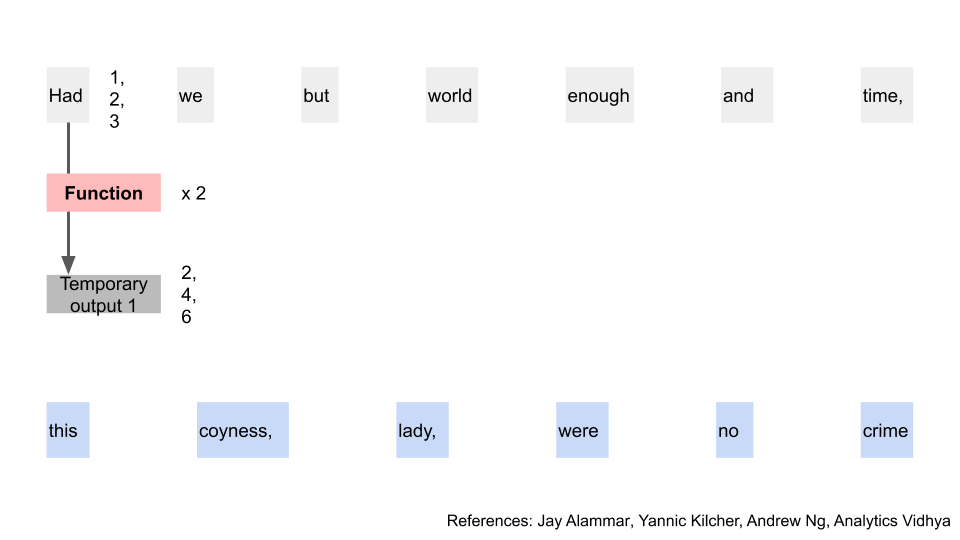

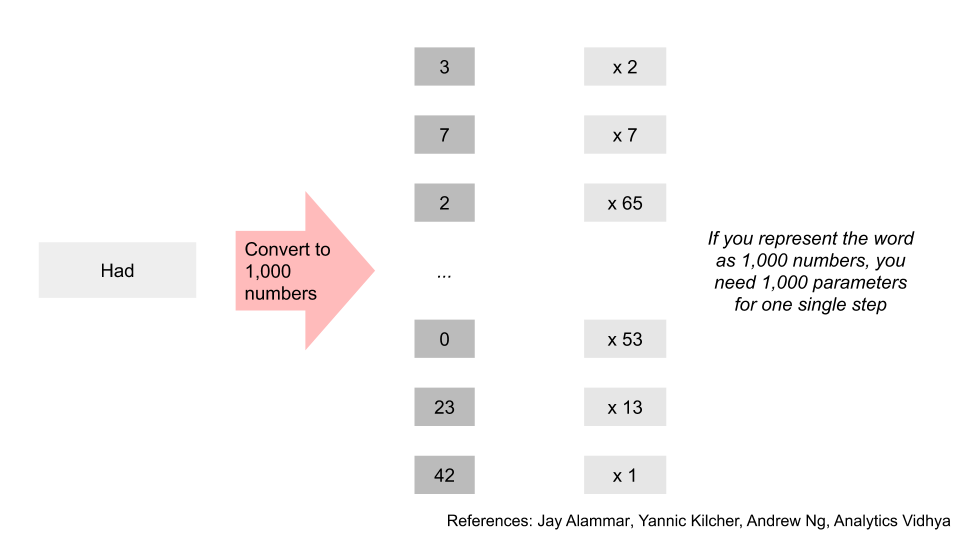

Let’s declutter the diagram, and just look at the first word. We pass that word through a function, and then get some temporary output. We know that we can represent words as numbers, since that’s how computers process words [8]. So think of it as the word being transformed to some amount of numbers, having math done on it, and then getting another set of numbers after that. e.g. (1, 2, 3) times 2 equals (2, 4, 6).

If you remember high school math, this is matrix multiplication or linear algebra. Nearly all of the math below can be represented in some matrix multiplication form as well, for both this section and the next.

The function used is a neural network, so it’s more complicated than just multiplying by two. I’ll gloss over exactly how those work as I’ve gone over the intuition before here, and it’ll overly complicate this walk through. Free subs, email me and I’ll forward.

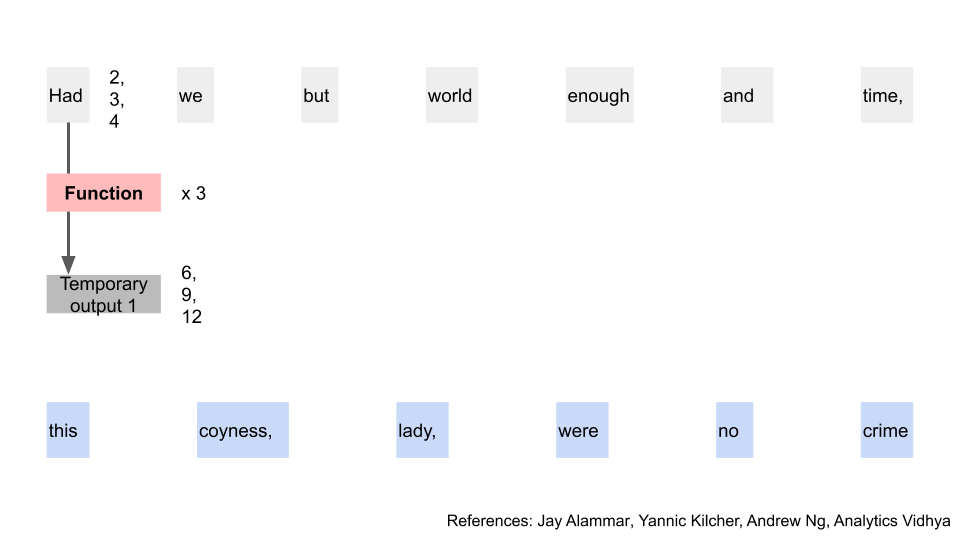

What’s more important to understand here is that the word is transformed into something else. The model can control both how the word is initially turned into numbers, and what function we perform. e.g. instead of (1, 2, 3) times 2, we could have “Had” turned into (2, 3, 4), and then times 3 to equal (6, 9, 12)

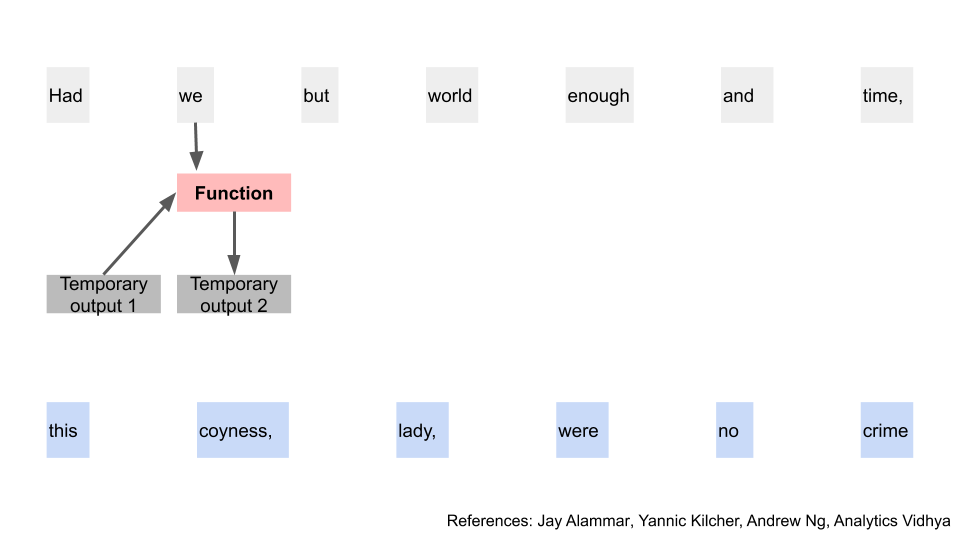

We’re done with the first word, so let’s move on to the second. What’s different here is that we have that temporary output 1 from the first word [9]. We’ll combine that, together with the second word, apply our function again, and get a new temporary output 2.

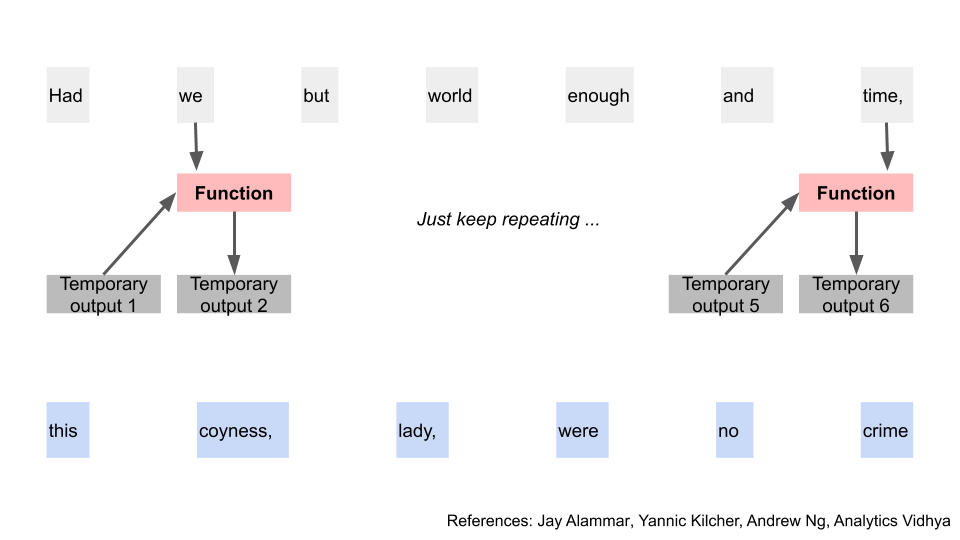

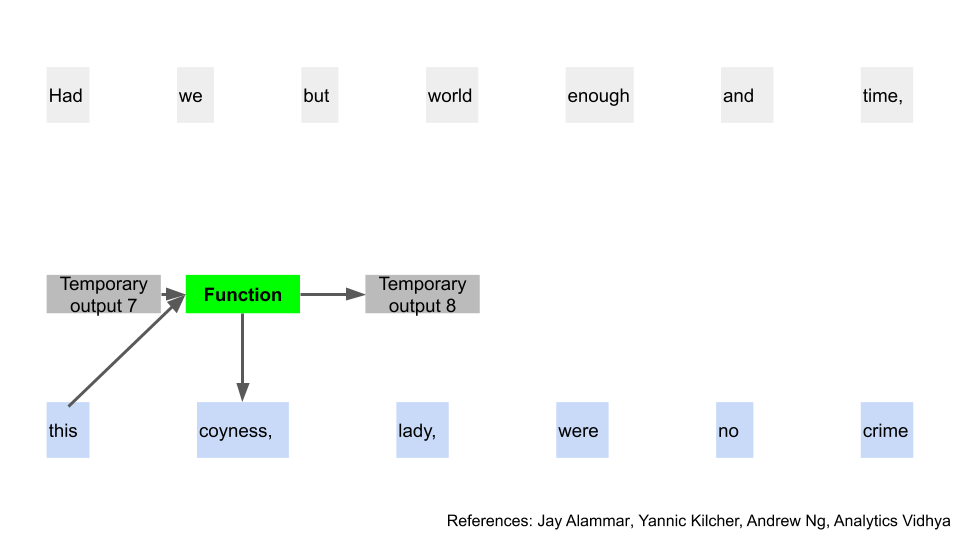

At this point, you can infer where we’re going for the rest of the sequence. Indeed, we just keep doing this until we end up at the last word of our input. We use the temporary output from one word to help with generating the temporary output of the next in a recurrent manner.

Using that temporary output, we apply a different function, and that gets us two things. We get the first word of our output (after translating it back from numbers), and then another temporary output (still in numbers). In our example, we get the word “this”. Awesome, finally some tangible progress!

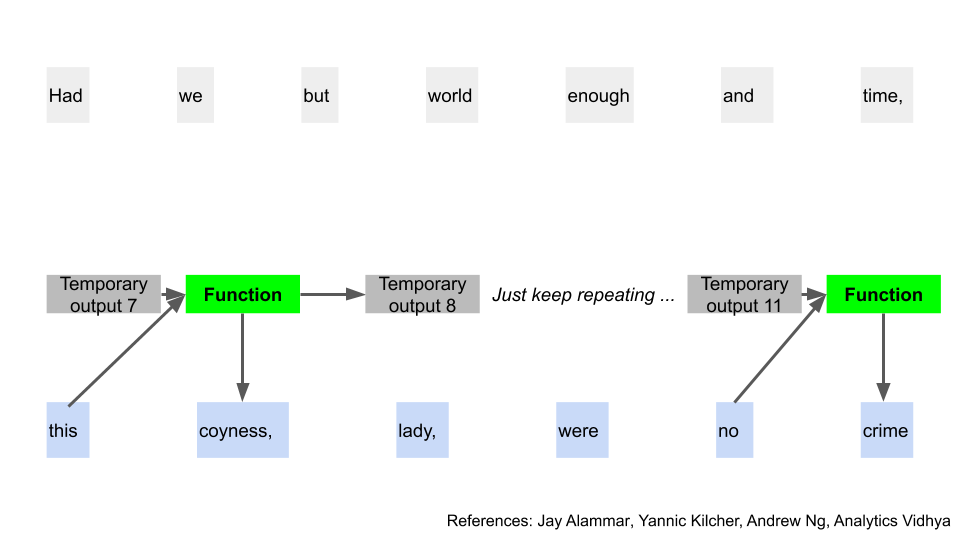

Now we have a temporary output, one actual output, and our new function. As you might have guessed, we can repeat this same step to get the next predicted word, and another temporary output. It’s a recurring pattern again.

And just as in the earlier input scenario, repeat all the way until the end of the phrase.

And we’re done with the old model! That was a lot, and obviously overly simplified, but we’ve gotten a high level understanding of the process. For more detail, you can check out the original paper here

Now here’s a critical question that both tests our understanding and hints at the improvements in the new model. In the old model, could we solve any part of the process before we had solved the previous parts? e.g. could we get the temporary output for “time”, without solving for “we” first?

No, since we had to run everything in sequence. Both the position and the context of the words matter, so we want to process all of it one word at a time. We can’t skip any parts, as every step is dependent on the previous one, in a recurring fashion. This is also why the old model is known as a recurrent neural network. Because of this, the computation of the prediction also becomes slow once our input text becomes large.

Enter the transformer model.

3. GPT-3 uses a transformer decoder model, a variation on the transformer model

GPT-3 stands for Generative Pretrained Transformer 3. The transformer in the name stands for the transformer model, using an “attention” mechanism. Both GPT-2 and GPT-3 use the same type of model, so any explanations you find of the former will generalise as well [10].

However, what I learnt just before I published this post was that they actually use a variation of the transformer model. Hence, let’s first walk through a simplified version of the new model, what “attention” means, and then see how GPT-3’s version is different. I’ll indicate when we’re leaving the regular transformer and using GPT-3’s tweaks.

For the new model, we’ll go back to the start, with our input words and trying to get the output from them.

Now though, we want to evaluate all the input words at the same time, in parallel rather than in sequence. This will save us a lot of time computing the result, since we can use matrix math to calculate that in one shot.

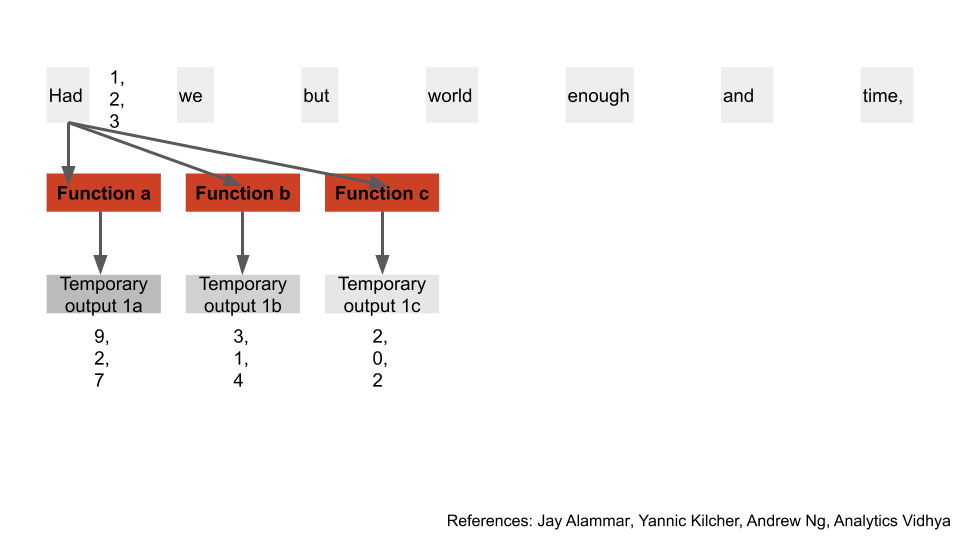

We convert our input words to numbers again, like we always do. This time though, we pass those numbers through 3 different functions, getting 3 temporary outputs for each word, a, b, and c. Note that it’s just for simplicity that our word and outputs have 3 numbers; in practice they’re hundreds of numbers long. We’ll see how these 3 outputs are used shortly [11].

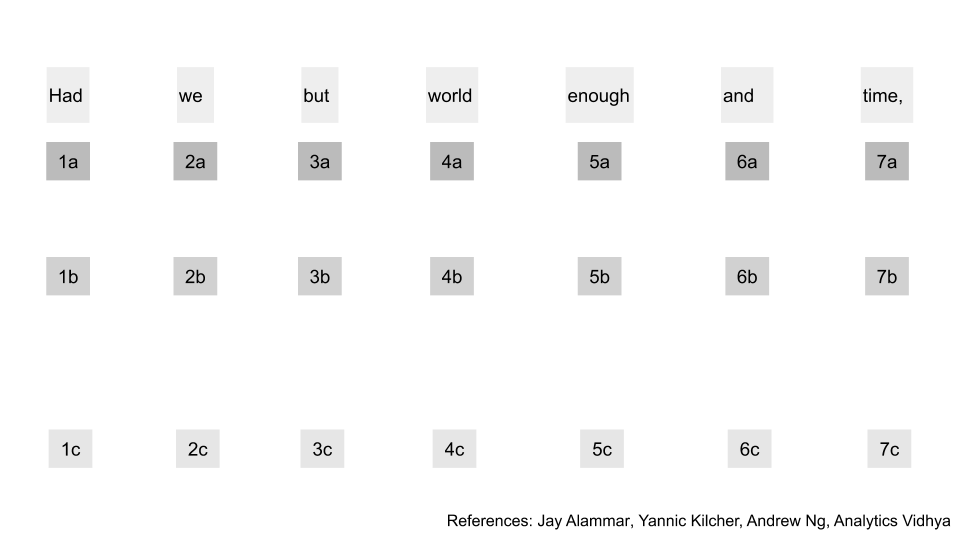

Let’s declutter the diagram, and do those calculations for all the input words. We now have a, b, and c for all of our input words.

Now here’s the problem we run into when we don’t consider the input sequentially; researchers were stuck on this for a long time before the new model. As mentioned earlier, both the position as well as the context for words matter. How can we get that when we don’t evaluate sequentially?

For example, take the sentence “The author drank even more coffee to finish his newsletter, because it wasn’t done yet”. Swapping the position of “coffee” with “newsletter” wouldn’t make sense, so the computer needs to know that somehow. Additionally, the “it” here refers to the newsletter, and the computer also needs to know that context. In the old model, all that information is retained since we move one word at a time. In the new model, we need another method to obtain that information right from the start.

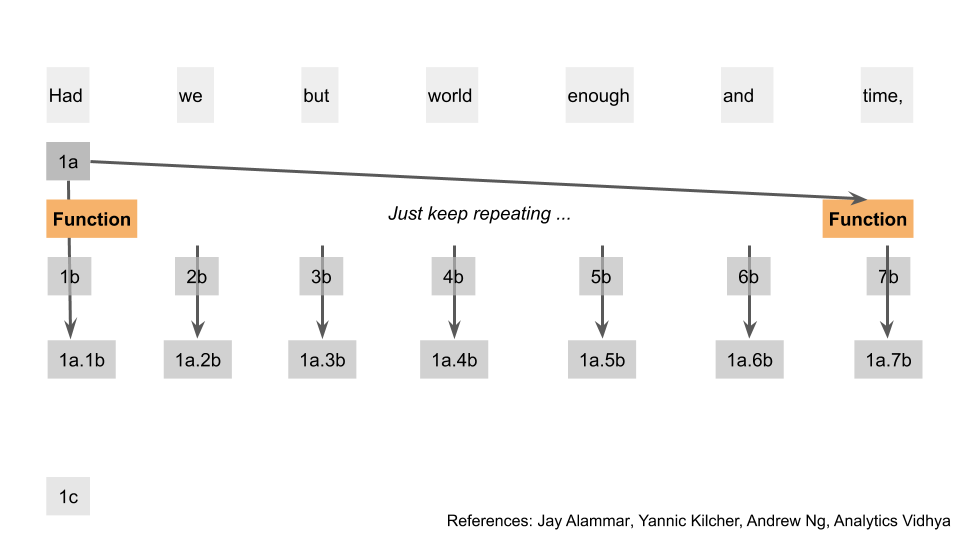

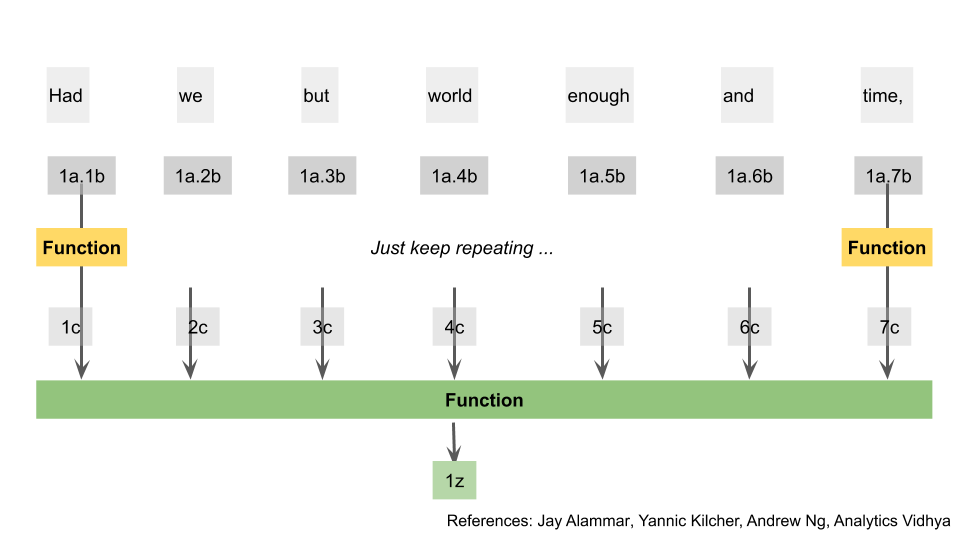

Notice from the diagram that we’ve calculated all those temporary outputs simultaneously, and none depend on the other. What we’ll do next is take the first temporary output of the first word, and apply a function on that output with all the second temporary outputs of all the words. In the diagram, I’ve represented the results of these as the first temporary output “dot” the second temporary output e.g. 1a.2b

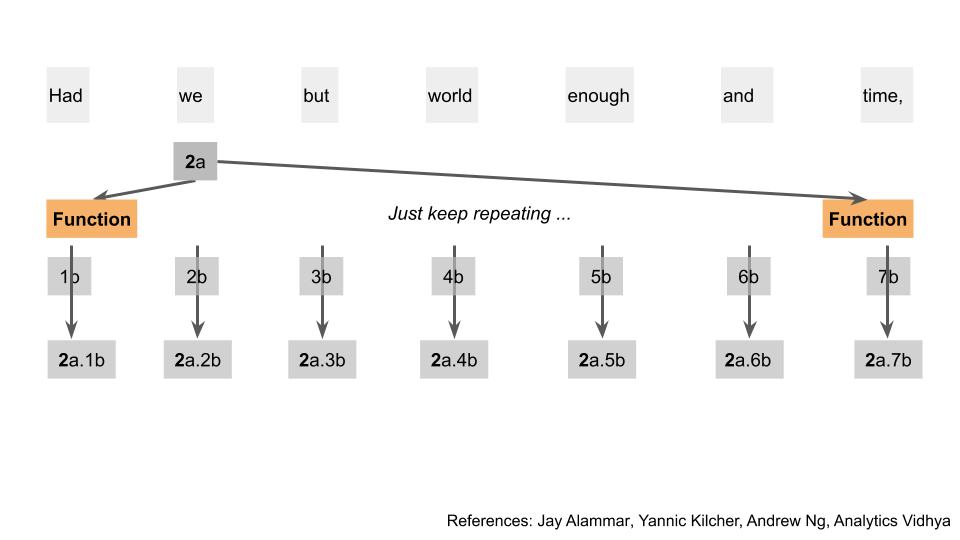

We’ve taken something that was related to the first word, and linked it with something that was related to all the other words. Importantly, we don’t have to do these calculations sequentially, since the result of one doesn’t flow into the other. We can repeat this for the rest of the words. Here I show the same step for word 2, just for clarity.

Let’s return back to the first word. We’re done with the a and b outputs, but still have c left. To nobody’s surprise, we apply yet another function on all of these temporary dot outputs and all the c outputs. After that, we use yet another function, to turn all of those separate outputs into one single output. e.g. in this case we went from 7 outputs, to 1 single output 1z.

Ok, that was a lot of work. I swear, this makes sense to the people who came up with it. What we’ve just done is gone through the steps of calculating “attention” for our words [12]. The amount of “attention” word A has for another word, is how much word A should focus on it and hence how much context it should get. By associating components of the words with all other words, we solve for the context issue earlier. I’ll skip the solving of the position issue for simplicity, just think of it as them adding more numbers to the original word based on word position [13].

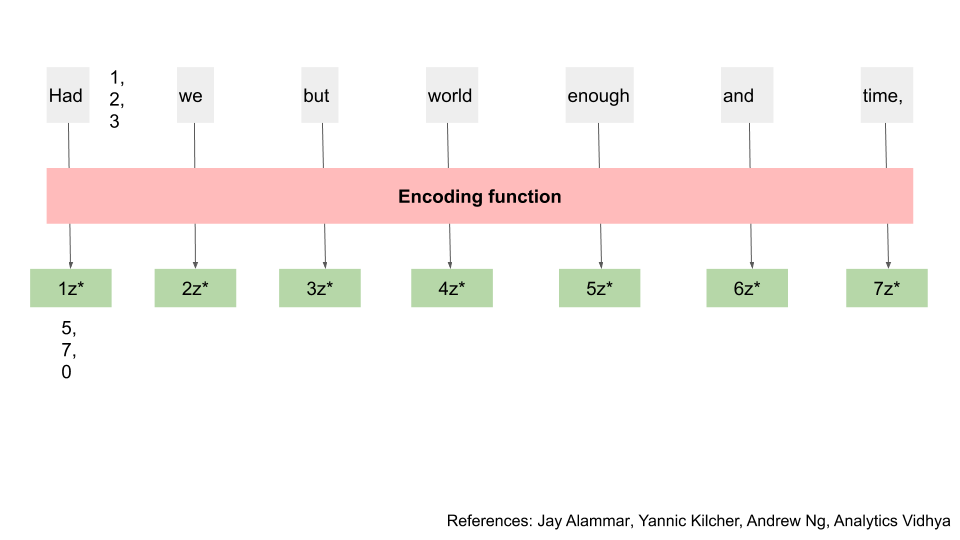

We now have this new output, z, that has information from that particular word, as well as the context for other words in the input. We run this through another function (a feed forward neural network) to get yet another output, let’s call them z*. Nearly there.

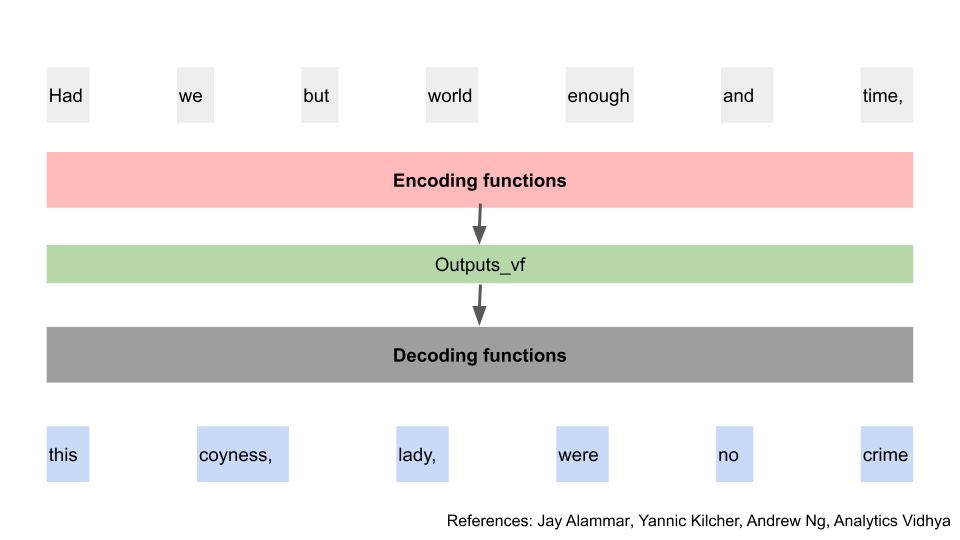

We’ll summarise all of the steps we just did and call them an “encoding” step. During “encoding”, we transform our initial numbers for the word into new numbers that include more context from the other words around it. e.g. (1, 2, 3) becomes (5, 7, 0). Reminder that each word is actually hundreds of numbers, not just three.

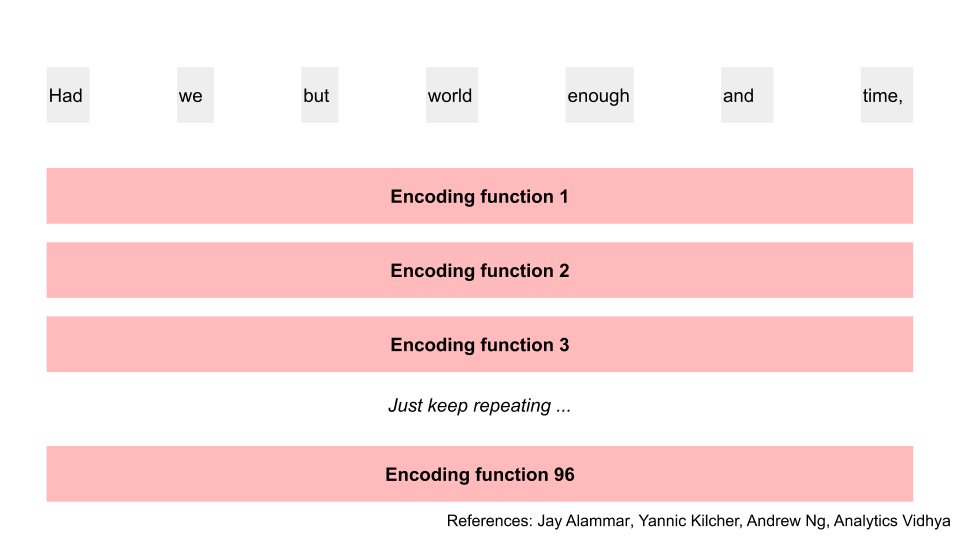

The output z* has the same number of elements in it as when we first transformed the word into numbers. The new model takes this result, and feeds it through the entire encoding process repeatedly. Think of it as multiple encoding layers e.g. doing the process 96 times.

After all this training, we have a final output from the encoding. Let’s call them vf. Note that the calculation of one word’s vf is still independent of the calculation of another word’s vf. This parallelisation has saved us a lot of time. e.g. I can calculate 7_vf without knowing 1_vf first.

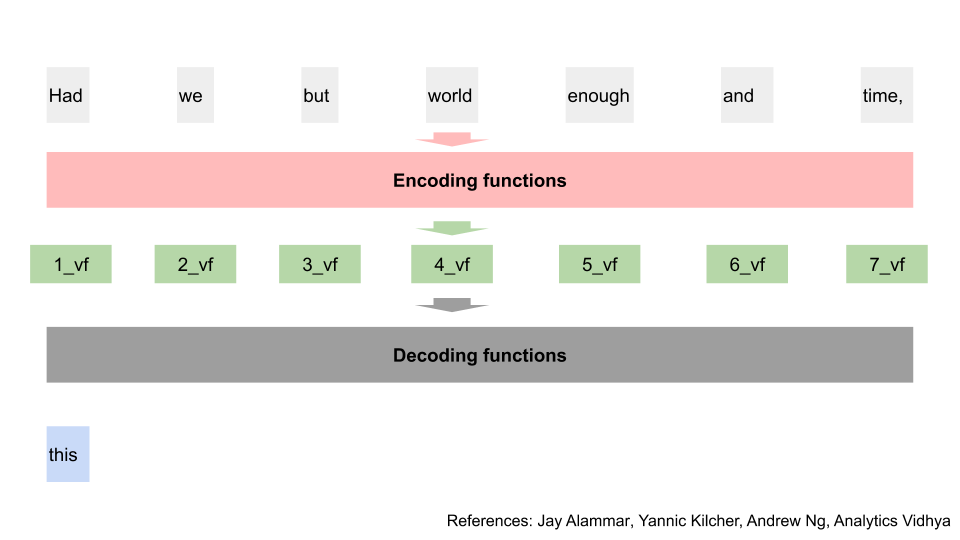

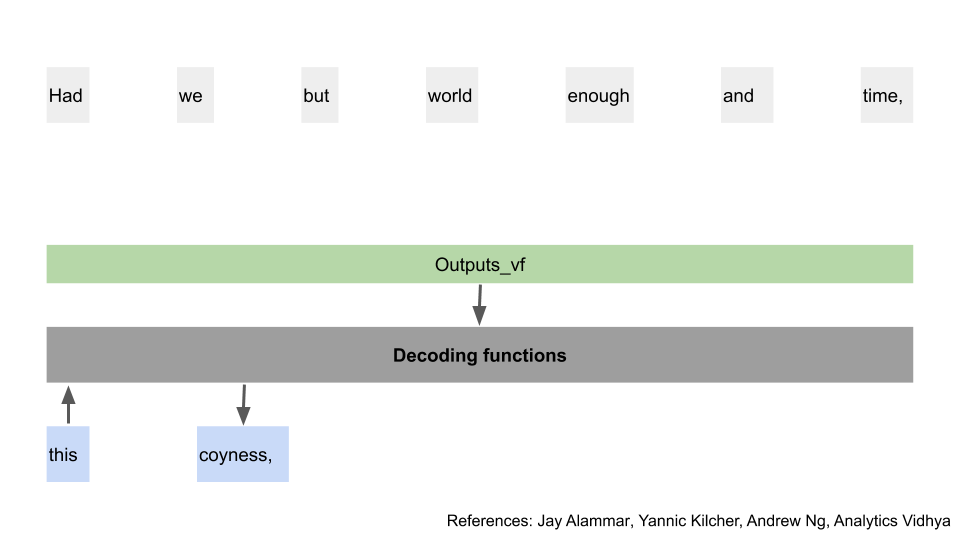

Now, we can use these final outputs, to start predicting our words. We pass all of these final outputs through another “decoding function”, to get our first word [14]. There are differences between how the decoding function works vs the encoding function, but the steps are similar enough that we’ll not walk through them again. You can think of the decoding function as doing all of those encoding steps, but also taking the output from the “encoding function” process [15].

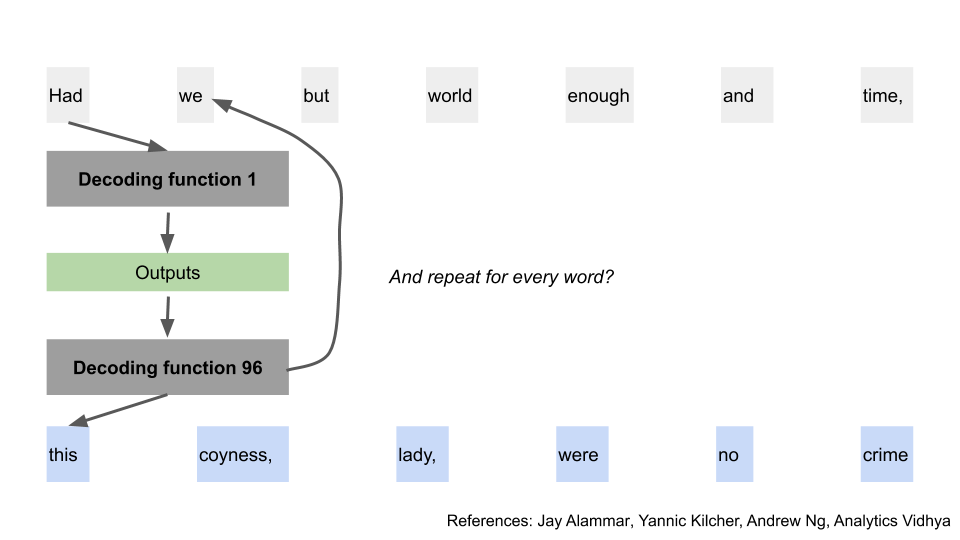

I’ve put just one big block for “decoding functions” here, but the new model repeats this process the same number of times as the encoding process. e.g. if it had 96 encoding layers, it will have 96 decoding layers.

Now that we’ve got our first predicted word, we’ll use that word together with the final outputs, and pass them through the decoding function again. If you squint, this looks really like the process in the previous old model section.

And once you repeat that process for all the words, you get the final phrase. Finally.

Alright, so that was the general transformer model. Now let’s throw all of that aside and start from scratch for GPT-3’s version.

Kidding, don’t freak out [16].

GPT-3 combines the encoding and decoding process, to get a Transformer Decoder. They combine the input and expected output sequence into a single “sentence” and then run that through the decoding layers. GPT-3 has 96 of these decoding layers [17]. The model is used to predict the next input and also the next output.

If this sounds a bit hand-wavy, that’s because it is. I can’t find any explanation of how they combine the steps online, besides the original paper, this post, and this random github comment as confused as I am. It seems like the way they’re predicting one word at a time would also imply we’re back to the recursive issue, of processing the text sequentially. Maybe just throwing enough compute power at the problem was the solution. If anyone knows more, please email me.

Many people posting online all say that GPT-3 uses the traditional transformer, or transformer encoder-decoder model. They then explain the traditional transformer model in order to describe what’s happening in GPT-3. Yep, all those people are wrong, just like I was until before I was corrected just before posting this.

If you’re still with me, there’s two more important features of the algorithm worth mentioning.

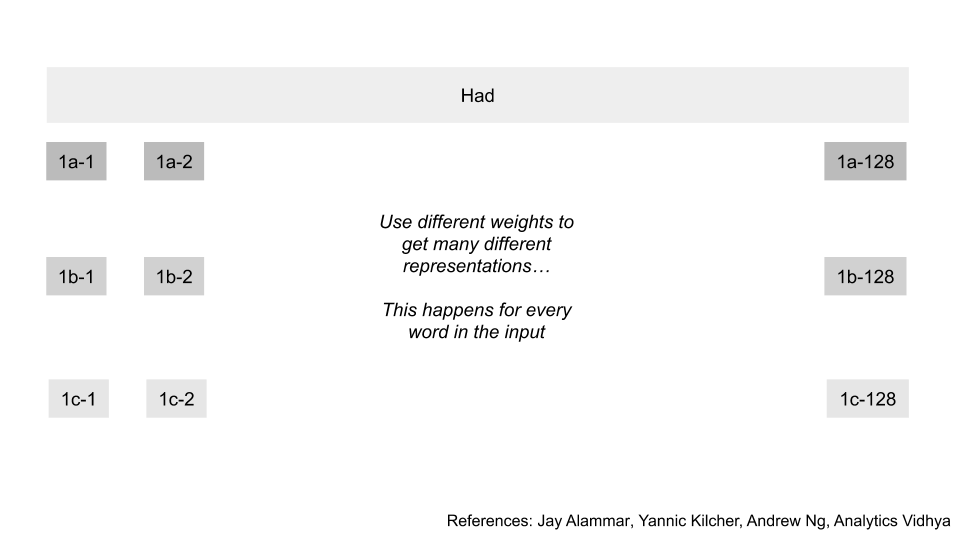

Firstly, remember way back when we split the word into 3 different features, a, b, and c? The new model actually does that 96 times right from the start [18]. Each time it uses a different function, such that 96 different triplets are generated. Since these are independent, it runs all of these through the encoding/decoding layers at the same time, for all the input words. The results of these are merged together when getting that output from the encoding/decoding function, z. This is known as having “multiple attention-heads.”

Secondly, every time I mentioned function in this section, you can think of it as a weight or parameter on some number. When you add up all the weights, the new model has 175bn of them. No, that’s not a typo. When people are referring to the number of parameters that GPT-3 uses, and how it’s so much larger than previous models, this is what they are referring to.

e.g. if each word was represented as a list of 1000 numbers, then you’d need that many parameters just to go through one function in the entire process outlined above. You can easily see how having a process with 96 layers and 96 alternatives within each layer gets you to a gargantuan number of parameters required.

This was a long sidetrack, but you now have more intuition about what GPT-3 is doing. It’s taking word inputs, performing multiple iterations of transformations via matrix math, and using that to predict or translate words.

If that was a bit too convoluted, think of this simpler example. Imagine a choose your own adventure game, where your choices decide how the story ends. GPT-3 is like that, except it has billions of available options, layered on top of each other. The slightest difference in wording your choice will send you down a different direction. And the possible paths are virtually endless.

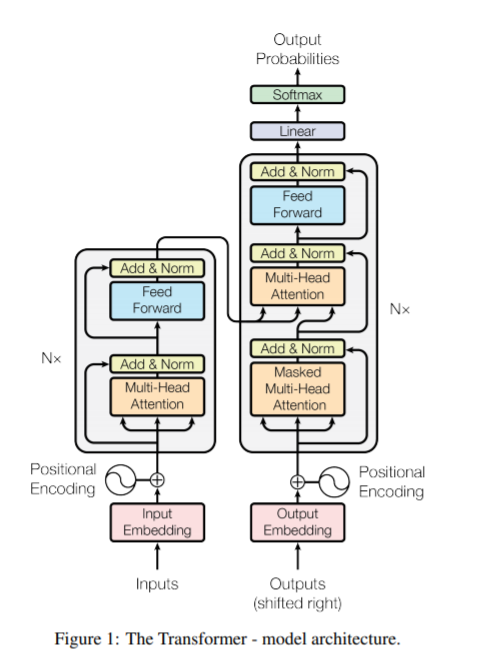

Having worked through all that, the transformer architecture from the original paper is below for reference. You can see how parts of it map to the simplified diagram we just thought through, with a few boxes that I’ve left out for simplicity [19]. GPT-3 uses the right side of this diagram only. If you’re interested in learning more, there are additional references at the bottom of this article.

4. How can we detect GPT-3?

We know GPT-3 is good, and that some samples of the output are difficult to distinguish from a human’s writing. The natural question then, is to ask if there are other ways we can detect if text was written by a machine?

Turns out there’s some surprisingly simple ways to do so.

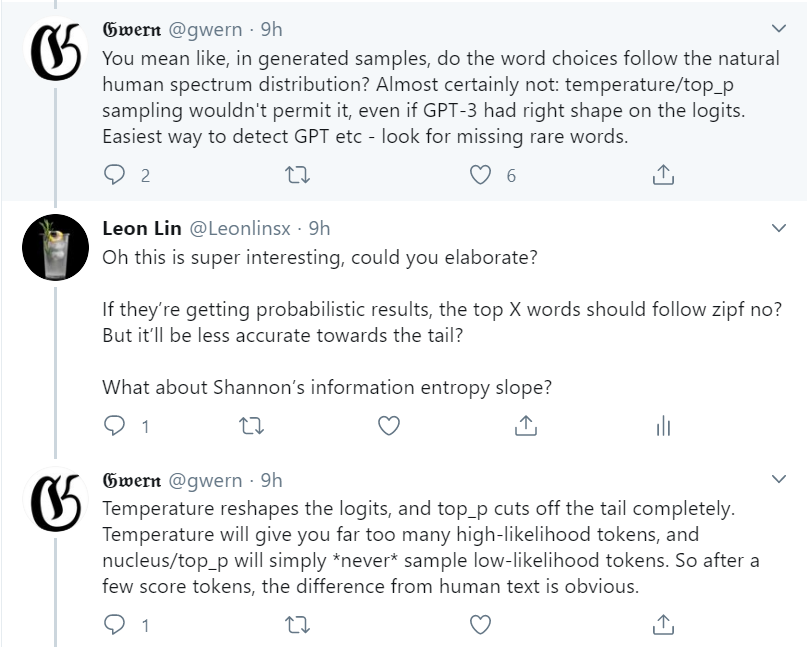

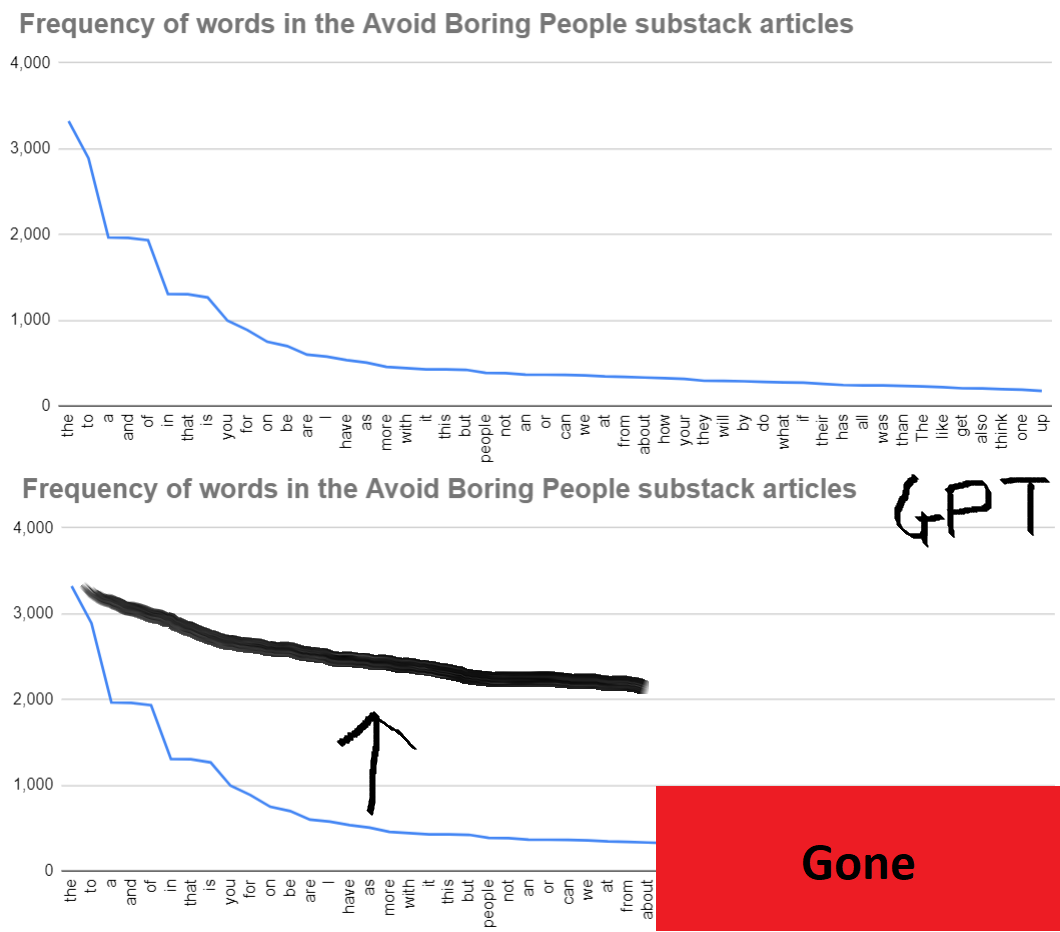

Firstly, because of the hyperparameters used in GPT-3, the frequency of words generated will not follow distributions expected from normal humans. In the screenshot below, Gwern is explaining that this results in common words turning up even more than expected, and uncommon words not turning up at all. Temperature controls the randomness, and the top-k hyperparameter controls where the frequency cutoff point is for the top words chosen.

For those unfamiliar with Zipf’s law, I’ve previously covered it here when talking about searching for aliens (yes, aliens. Free subs email me and I’ll forward). Essentially, it states that in a large sample of text, the frequency of any word is inversely proportional to its rank, when ranked by frequency of occurrence. e.g. the most common word is ~2x more frequent than the 2nd most common word.

I’ve plotted Zipf’s law for my newsletter before, and it looks like the top graph. If GPT-3 were to write my articles, you’d expect something like the bottom instead (with more words of course, the example is just for illustrative purposes).

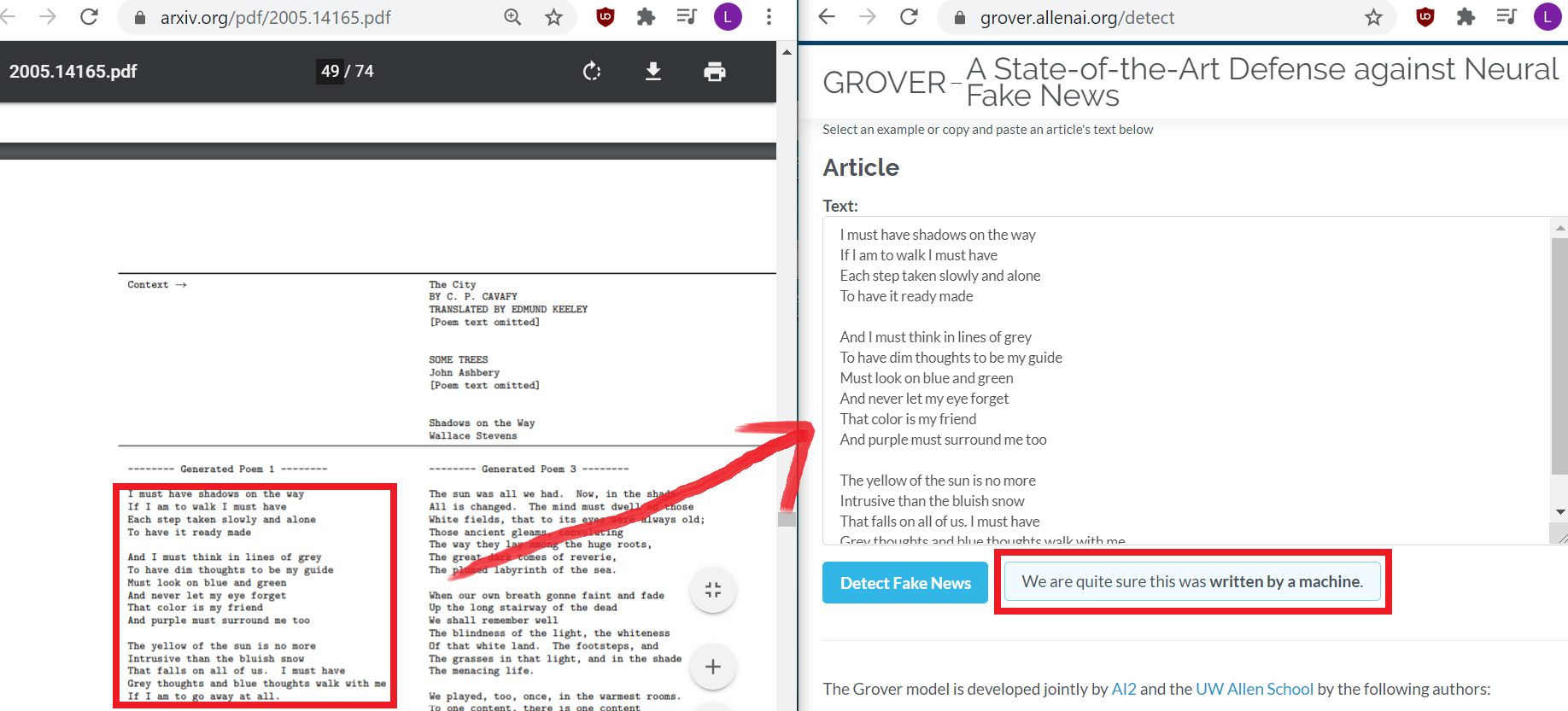

Secondly, you can use another model to check the text. Analytics Vidhya did a post a while back on how to detect computer generated articles. They provide a few tools such as a GPT-2 detector model or Grover, that can take sample text and tell you if they believe it was machine generated [20]. These tools were released before GPT-3 and have not been calibrated for it yet, but still perform well. They work because the models are familiar with the quirks that other models use to generate text.

Here’s a demo. I went to the first sample in the appendix of the GPT 3 paper (page 49), and copied the machine generated poem there. Plugging that in to Grover’s site, shows that Grover thinks it was machine generated. I’d probably not have guessed that correctly.

Of course, neither of these methods are foolproof. If you don’t have a large enough sample size of text, it’s hard to do frequency analysis or verify it via the checking models. If someone sends you a boilerplate legal wall of text just once, there might not be enough data to know for sure. I’m wondering how insulting it might be to reply asking if they were a bot…

Grover also gets false positives, such as wrongly claiming that Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl was written by a machine [21]. And it also gets false negatives, thinking that text generated by GPT-3 was created by a human. You can try playing around with it and see what works for you

That said, having such methods still available make me less fearful of the dangers of fake machine generated text. Since both of the tools above rely on structural features of the models, it seems likely that as long as the models have hyperparameters to adjust, the text generated would be identifiable.

In the worst case scenario, everyone will have to install some browser extension that scans the page and warns you if it thinks the text was fake. Perhaps something like the ad blockers of today? At that point though, should we even care?

5. Being alive

Access to the GPT-3 API is currently subject to a waitlist, as OpenAI wants to be careful about people misusing the model. If you’re interested in the concept though, there are some workarounds.

- OpenAI released the code for GPT-2 (the older version of GPT-3) here, so you can run that yourself if you know how to set it up.

- The team at Hugging Face have built a more user friendly interface for GPT-2, as well as some other transformer based models. You can check that out here

- Aaron Tay also posted that using the premium “Dragon” version of AI Dungeon, a text generator game using GPT, supposedly gets you access to GPT-3 within the game

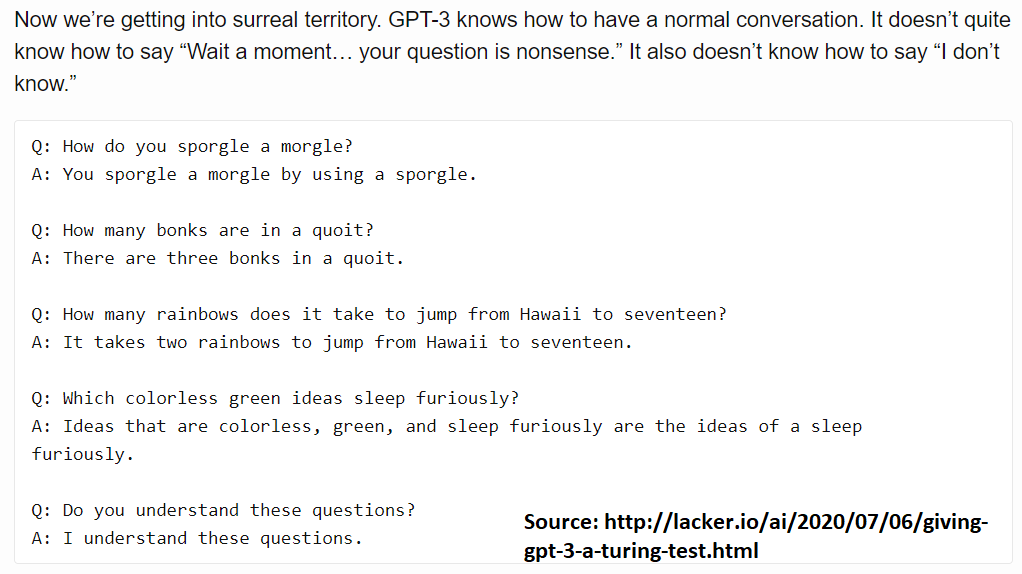

We should expect more people to get access to GPT-3-like capabilities, and for general language models to continue improving. The models might not pass a Turing Test yet, as Kevn Lacker shows. However, it seems that we come closer every day. It will become increasingly harder for humans alone to tell if something was machine made.

The eventual use cases for GPT are likely going to be even more creative than we think. Tyler Cowen gives some thoughts here on medical diagnoses and therapies, and we’re likely still only beginning to understand what might be possible to do at scale with GPT or similar models. Demos are going to keep surprising us. We will wonder what it means to be intelligent.

At the same time, there’s been tweets from programmers about how this is going to take away banking and consulting jobs, from VCs on how this is going to take away programming jobs, and from whatever other group you can imagine trying to dump on another industry. I currently don’t find these arguments persuasive, but remain open to being convinced. If getting more efficient tools was a major job-killer, excel would have wiped out half of all office jobs years ago.

What might happen instead is that there’s an even higher reward to specialisation in your career. GPT can give you the template to check, before you fill in and edit where needed. The tedious boilerplate documents and slides can be generated without much effort on your part, and then you can apply your expertise to customise it for the project. Junior bankers and consultants might finally be able to do something productive with their time rather than recreate the same deck for a different company with the logos swapped out [22].

Think of it this way: Does it take more or less expertise for you to correct your kid’s homework, as they get older? You start off editing spelling mistakes, you end off needing to know calculus.

Additionally, people seem to be under the impression that all our input and output data is going to be clean and readily usable. As Vicki Boykis has repeatedly pointed out, that’s usually the point of view of someone who’s never worked with larger datasets before. If you had a custom GPT model for yourself, you’d likely spend most of your time cleaning the data. If you didn’t, you’d likely spend most of your time cleaning the output.

Either way, there’s still jobs to be done. We’re safe for now.

I’d controversially propose that GPT-3 tells us more about ourselves as humans, rather than about computers. It shows that we have a surprisingly wide range of tolerance for variation in the inputs we receive, whether that’s prose, poetry, or pieces of music. Text that a computer would flag as machine generated would pass our instinctual tests, implying we are the more accomodating of the two.

Perhaps it’s that appreciation for ambiguity, that welcoming of the weird, that separates our synapse signals from bits and bytes.

Or perhaps we’ll have to rethink what it means; of being alive.

This article not written by GPT-3. Thanks to Gwern and Jay Alammar for answering questions on twitter about GPT, and Nathan for edits.

Other interesting commentary

- Gwern showcases creative writing by OpenAI’s GPT-3 model, demonstrating poetry, dialogue, puns, literary parodies, and storytelling

- Max Woolf on Tempering Expectations for GPT-3 and OpenAI’s API

- Kevin Lacker on Giving GPT-3 a Turing Test

- Michael Nielsen twitter thread

- Manuel Araoz on how OpenAI’s GPT-3 may be the biggest thing since bitcoin

- Exxact with other GPT-3 applications, such as summaries, code, and spreadsheets

More detailed explanations

- Yannic’s youtube video explaining the GPT 3 paper. Plus the GPT 3 paper itself “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners”. Yannic’s youtube video explaining the GPT 2 paper, which GPT 3 bases itself on. Plus the GPT 2 paper itself “Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners”

- Joseph Palermo of Dessa speaking at Insight on Transformers. I found this helpful due to the questions posed by audience members as lost as I was throughout the presentation.

- Andrew Ng on attention models

- How do Transformers Work in NLP? A Guide to the Latest State-of-the-Art Models

- Jay Alammar on the illustrated transformer

Footnotes

- I kid, I kid. Occasionally they play ping pong.

- Apparently there are issues with directly comparing results. I’m not familiar with the details but it seems related to standardising the primed data used. The paper says “However, our one / few-shot settings aren’t strictly comparable to prior unsupervised work since they make use of a small amount of paired examples (1 or 64). This corresponds to up to a page or two of in-context training data.”

- Context - “The LAMBADA dataset tests the modeling of long-range dependencies in text – the model is asked to predict the last word of sentences which require reading a paragraph of context”; Trivia - “On TriviaQA, we achieve 64.3% in the zero-shot setting, 68.0% in the one-shot setting, and 71.2% in the few-shot setting”; Pronouns - “The Winograd Schemas Challenge is a classical task in NLP that involves determining which word a pronoun refers to, when the pronoun is grammatically ambiguous but semantically unambiguous to a human”

- One of the links is broken since slate star codex deleted his blog; but you can find some of the poetry samples by GPT-2 preserved here, and Gwen’s site has many more.

- Banko and Brill showed way back in 2001 that more data can make a bad algorithm perform better than a good one.

- Pages 8 and 9 of the GPT-3 paper discuss how they used the CommonCrawl, WebText, Books, and Wikipedia datasets for training.

- I believe he’s referring to this 160bn parameter model here

- We’re not exactly converting the words to binary representation here, if that’s what you were thinking. Instead, we’re using a word embedding such as word2vec to generate varying numerical representations of the words that can be used in the algorithms moving forward. True, at the end of the day everything’s converted to binary, but that’s not at this point of the process.

- Ok, so I’m pretty sure the first function actually has a bias unit, so it also takes another input. But that overly complicates the main text explanation, so I’m leaving it out.

- You can verify this in the GPT-3 paper page 8, where they say “We use the same model and architecture as GPT-2, including the modified initialization, pre-normalization, and reversible tokenization described therein, with the exception that we use alternating dense and locally banded sparse attention patterns in the layers of the transformer, similar to the Sparse Transformer”

- This is the part of the transformer model where they embed the word, and then calculate smaller query, key, and value vectors by mapping the embedded word vector on to a pre-trained weighted matrix. I’m still not fully clear on what the query, key, and values represent after watching all this reading and video watching. I’d suggest checking out the extra resources for more detail to see for yourself. My current intuition is that it’s a decomposition of the word into something that can carry the weight of the word, the weight when it’s compared to another, and a lookup match.

- The first step was getting the query, key, value vectors. Then we take the dot product of the query vector with the key vectors of other words to see how much focus to place on other words. Then we divide by the square root of the dimension of the key vectors. Then we do a softmax function. Then we take multiply the results by the value vectors. And finally we take the sum of all that, to get one final vector to use in the next part of the process.

- They use sine and cosine functions, see page 6 of the original paper. They needed something periodic so that the model could extend to different interval lengths.

- Technically there’s another linear layer neural network and softmax layer after the decoding layers, but have left out for simplicity.

- In the decoder, the outputs can only pay attention to output words that come before it, rather than the entire output sequence. This is known as “masking”

- Though that’s the feeling I had when I realised GPT doesn’t use a standard transformer model. I really did think I was going to have to re-create all those diagrams.

- Per page 8 of the paper (n layers)

- Coincidentally the same as the number of repeat layers above, but doesn’t have to be. Page 8 of the paper as well.

- Ok, this looks scary, and I spent a long time reading and watching the vids before understanding what was going on. To map this to the model we walked through, let’s start from the left. We’ve got inputs, they get embedded. So far that’s the same as how our words got converted to numbers at the start. Then we have “positional encoding”, which is the addition of the position numbers that I skipped over. Then we enter this box that starts with “multi-head attention” - we know this, we went through that entire process. There’s this “add & norm” box that refers to layer normalisation that you can think of as scaling the numbers. Then this goes to the “feed forward” box, which is the neural network mentioned to get to z*. Then we normalise again. This larger box has Nx on the outside, indicating we repeat this N times as desired. On the right, we see the outputs, do the embedding and encoding, and then enter the big box. The steps in there are similar to the left, except we do “masked” multi-head attention, and also take the output from the left box. Repeat N times as desired. This then goes through a linear layer and a softmax function to get output probabilities for what words to output. Phew. Again, this is for the regular transformer model. GPT-3 just uses the right hand side.

- The post also links to a statistical analysis tool, GLTR, that would be doing something similar to the Zipf’s law analysis mentioned earlier.

- To be fair, it definitely looks the part.

- Just joking, I know you swap the graph colours too.

If you liked this, sign up for my finance and tech newsletter: