Improving forecasts and incentivising communists

*This is an adapted post from my email newsletter. Sign up here*

This month is about getting better at forecasting, incentivising a communist, and developing into a better adult.

Better forecasting

We see people make predictions all the time, from finance to economics to politics. And although most of these forecasts and forecasters end up wrong, we continue to listen to them [1]. Are there people that can reliably forecast? This article focusing on Philip Tetlock’s [2] work on the subject claims there are:

Reliable insight into the future is possible, however. It just requires a style of thinking that’s uncommon among experts who are certain that their deep knowledge has granted them a special grasp of what is to come.

The article starts with an anecdote about Paul Ehrlich and Julian Simon’s errors, and goes on to detail Philip’s work:

Tetlock decided to put expert political and economic predictions to the test. […] The project lasted 20 years, and comprised 82,361 probability estimates about the future.

The result: The experts were, by and large, horrific forecasters. Their areas of specialty, years of experience, and (for some) access to classified information made no difference.

Because of the lack of accountability in forecasting, incentives are skewed towards making extreme predictions. If you’re wrong, people will forget. If you’re right, you get to ride the success of your one big call even years down the road. We’ve seen this from high profile hedge fund managers to economists, who made their fame on calls that seemed genius in hindsight but have struggled since. The ones that were incorrect wait a while to make new dramatic claims in a renewed hope for attention. As Paul Samuelson has been quoted, “The stock market has forecast nine of the last five recessions.”

The integrators outperformed their colleagues in pretty much every way, but especially trounced them on long-term predictions. Eventually, Tetlock bestowed nicknames (borrowed from the philosopher Isaiah Berlin) on the experts he’d observed: The highly specialized hedgehogs knew “one big thing,” while the integrator foxes knew “many little things.”

You might have seen this fox vs hedgehog comparison; it’s somewhat similar to the specialists vs generalists framework I’ve commented on before. However, though foxes are supposedly better at predicting, I still think that you generally get rewarded more for being a hedgehog. The perception of ability might be more important than having ability. Would be interested to hear your take on this.

Tetlock and Mellers found that not only were the best forecasters foxy as individuals, but they tended to have qualities that made them particularly effective collaborators. They were “curious about, well, really everything,” as one of the top forecasters told me. They crossed disciplines, and viewed their teammates as sources for learning, rather than peers to be convinced.

I’ve met plenty of people that believe they’re open-minded, saying they prefer getting to the truth rather than being right. Most of the investing community believes they have this mindset, since it’s almost a necessity to make money over time. Here’s something to think about though: What’s the last major thing you’ve changed your mind about? If, like me, it’s hard to come up with a good example, perhaps we’re not as open-minded as we thought… [3]

Whaling and incentives

The article claims this was “one of the greatest environmental crimes of the 20th century”:

in 1986, the Soviets had reported killing a total of 2,710 humpback whales in the Southern Hemisphere. In fact, the country’s fleets had killed nearly 18 times that many

To put the number above in context, the WWF has the current recovered humpback whale population at ~60,000. Pacific Standard has the full story, summarised on marginal revolution.

In most cases of illegal poaching, the culprit is demand for the animal’s parts. Think rhino horn, elephant ivory, shark’s fin. In this case though, Russia did not want the whale parts much, if at all:

the Soviet Union had little real demand for whale products. Once the blubber was cut away for conversion into oil, the rest of the animal, as often as not, was left in the sea to rot or was thrown into a furnace and reduced to bone meal

Why did this happen then? The full story shows the power of incentives working in a complex system:

the progress of the whaling fleets was measured by the same metric as the fishing fleets: gross product, principally the sheer mass of whales killed.

Whaling fleets that met or exceeded targets were rewarded handsomely, their triumphs celebrated in the Soviet press and the crews given large bonuses. But failure to meet targets came with harsh consequences.

If I was a ship captain and knew that all that mattered was exceeding my mass target year over year, of course I’d do everything I can to do so. Why bother about what my catch is used for, or the long-term consequences of my fishing, as long as I was rewarded?

[A fisherman] warned the minister that if the whaling practices didn’t change, their grandchildren would live in a world with no whales at all. “Your grandchildren?” Ishkov scoffed. “Your grandchildren aren’t the ones who can remove me from my job.”

Even in a communist system, people react to incentives (of course they do!) and will try to optimise for what they think is the best case outcome for themselves [4]. As I’ve written before, understanding what and how people are motivated is key to understanding why systems end up with the outcomes they do. If you think such a scenario can’t happen in today’s world, think about how company executives are incentivised to run companies and what metrics they are measured by.

Better mental habits by Jennifer Berger

I don’t like linking to podcasts since they’re more attention intensive than text [5], but this recent one on Farnam Street interviewing Jennifer Berger is worth the time. I don’t have access to the transcript, but some paraphrased highlights below:

Over time, you develop an increasing view of the world. Earlier in our lives we’re absorbed with the perspectives outside of us, and look outside to see what to do, we take them in as our own. As the world gets more complex, we move from this socialised system to a self authored one, we write our own story with our own internal system. Over time, even that breaks down for some people, we give up the protection of a single system of our own, and in a self transforming system it’s about looking across multiple stakeholders and create new possibilities people stuck in their own perspectives cannot see.

I didn’t have time to dig into this but it was an interesting framework to think about. This comes from Kegan’s theory of adult development [6] if you want to dig in further.

So many leadership courses ask you to name your own values, as though that’s something you discover, compared to something that you become as you find it. You don’t say to little children “I’m dissapointed you’re not running like an 18 year old” but we say that to adults all the time.

A charismatic leader makes you feel good about him or her. A great leader makes other people better.

A leader who feels certain cannot be learning from others.

Oh hey a callback to the first topic above.

We tend to be looking for the root cause of something, but in complex things there’s no root cause for anything.

In a predictable, linear world, one unit of effort leads to one unit of return. In a complex world, you don’t know, and you’re always feeling around to figure out what little thing will lead to an outsized effect.

You can’t tell tell the difference in brain scans of people recognising an opinion vs a fact.

Seek systems, take multiple perspectives, and ask questions to develop.

If you’re an expert and in a predictable place, go for it. If you’re in an unpredictable place, you have to realise that, as everything will go off the rails. If you find yourself in a meeting and there’s someone disagreeing with you, that’s great because you now have two perspectives. Get better at catching yourself drawing conclusions too quickly.

With the popularity of root cause analysis being taught in business schools, I like how she points out that complex situations may not have a root cause. We all prefer simple cause and effect loops, such as blaming a politician for the economy or an event for subsequent consequences. This is convenient but usually mistaken.

Miscellaneous

-

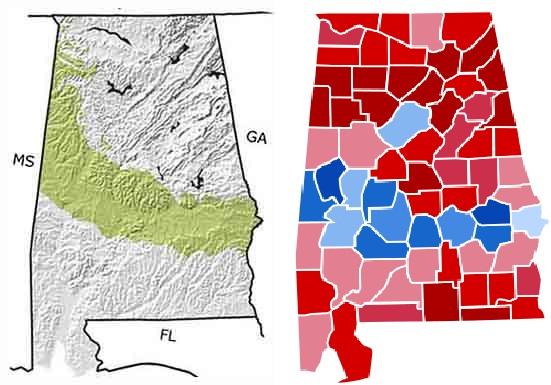

How the Cretaceous Period seashore affects how Alabama votes. The green on the left is the old seashore; red/blue on the right is party votes. More context here

-

- Given the rise of JUUL and alternatives, it’s encouraging to see studies showing “E-cigarettes were more effective for smoking cessation than nicotine-replacement therapy”

- “Gobi Heaven is not the first attempt to profitably copycat Burning Man in China”

- Psych studies usually have replication issues, but caveat aside, experiencing awe might increase pro-social behaviour

Footnotes

- Some famous quotes here and here showing how predicting the future is hard, even for people who are experts in their field. I’m not listing this to shame; I’d probably have been even more wrong in their situation.

- Naturally, there are critics of Philip’s work, with Nassim Taleb being a particularly outspoken one. Both have published books and tweeted about their work, if you’re interested in digging in further.

- I’m not saying you should change your mind all the time. But it is remarkable the number of people who will claim they have ‘strong opinions, weakly held’ that also can’t say the last time they’ve had a change in opinion.

- Emphasis on think. Most people, myself included, are bad at knowing what’s best for ourselves.

- That said I wonder how many people actually click through the links anyway…

- For further reading, check out this medium post that was the highest ranking search result. I can’t find the original papers and am annoyed by that.