Not everything is insider trading

Takeaway

Your investment edge as a retail investor should be different from a professional investor.

Using data in investing

Last week, we looked at how companies use machine learning to take data, process it, and come to a conclusion.

This week, we’ll look at a more human oriented process. We’ll walk through how analysts at an investment firm obtain data, analyse it, and form an investment thesis. With investors spending >$30bn on data, where is all that money going to?

I’ll be doing this from a typical long/short fundamental hedge fund point of view, rather than a quantitative firm [1]. For convenience I’ll also be discussing this from a US company perspective, though the general process below applies internationally.

My goal is for you as a retail investor to have a better understanding of the edge that professionals have, and what that implies on the edge that you can have [2].

Public data

Publicly listed companies have to file financial statements regularly with the SEC. These are publicly available on both the company investor relations pages and SEC Edgar for you to search through.

Companies also hold regular earnings calls for each major earnings announcement, which anyone can dial into [3]. The call transcripts can sometimes be found on the investor relations pages as well, or at sites like Seeking Alpha. However, they can be harder to track down than the financial statements.

Companies usually release news via PR newswire while also posting it on their own website. Such news could be the financial filings mentioned above, or special events such as acquisitions and management changes. The news gets distributed via PR newswire to other news sites.

Besides the public data mentioned above, an analyst would spend time taking in twitter, googling google, or reading reddit. They compile all of these primary sources together to form an opinion on whether to invest in the company.

This is one part of the investment research process, the discovery and usage of publicly available information that everyone can do as well. From the above, you already have enough data to build a company financial model, analyse trends, and form an investment thesis. In fact, many retail investors never go beyond this part, and still do well for themselves. As I’ve mentioned before, there’s many ways to be successful in investing.

Access to public data

So if that’s all that’s needed, why do so many other companies exist to provide information to investors? How does Bloomberg make $20k a year from a single subscription?

Well, it turns out that:

- Obtaining data directly from SEC Edgar is a huge pain

- People always want more data, since they believe more data is better

- There’s a lot of other non-public data that you can buy

In this section I’ll discuss the first point, that of the user experience.

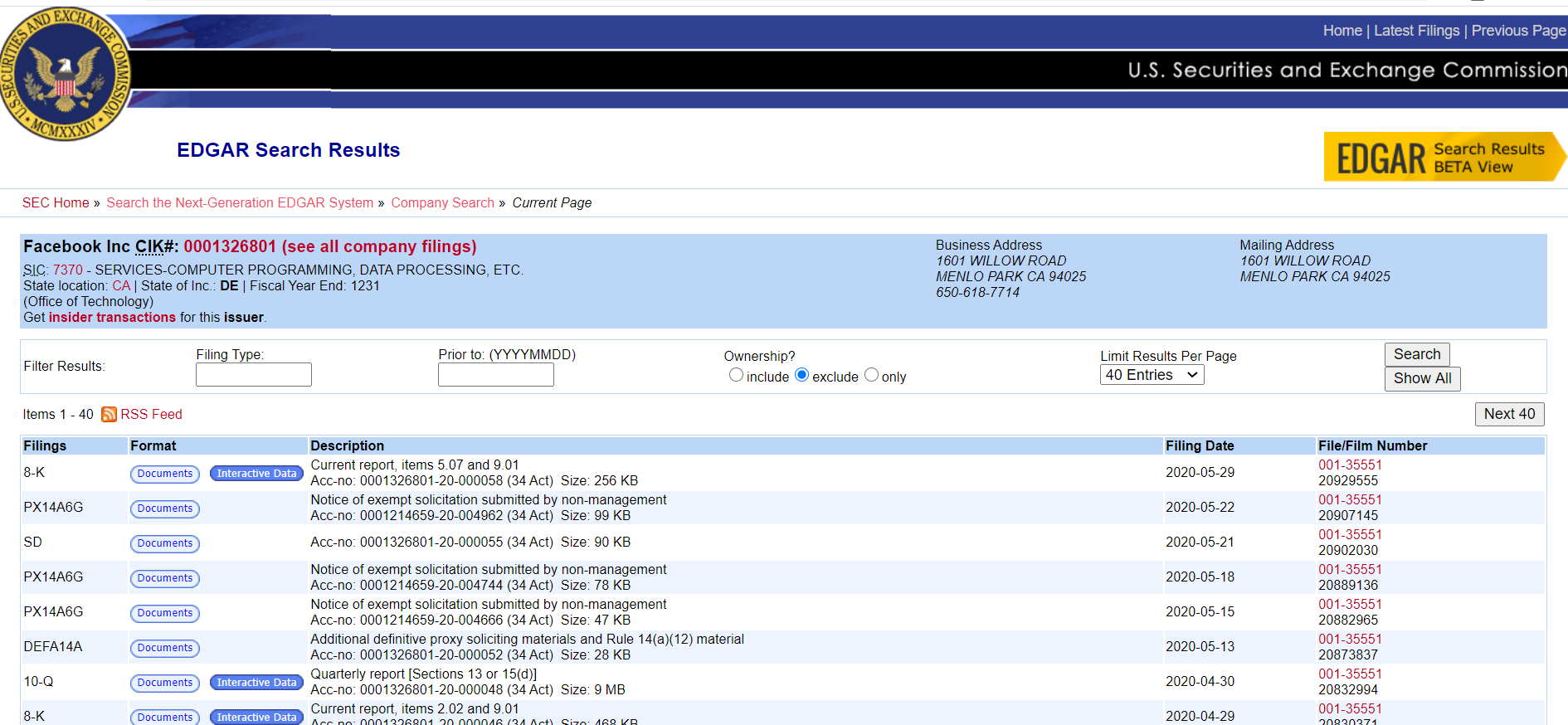

Let’s say you wanted to quickly look at a company’s revenue over time. If you did it the traditional way on Edgar, you’d have to search for the company, resulting in a page like this:

You’d then have to look for each filing you wanted, download all of them, and copy the data into a spreadsheet [4]. After you cleaned the data and added in rows to do the year over year calculations, you’d finally get the trends you wanted.

That was a lot of work for very little payoff, which is why companies like Bloomberg, FactSet, Thomson exist. They gather financial data, and have it easily accessible within the platform.

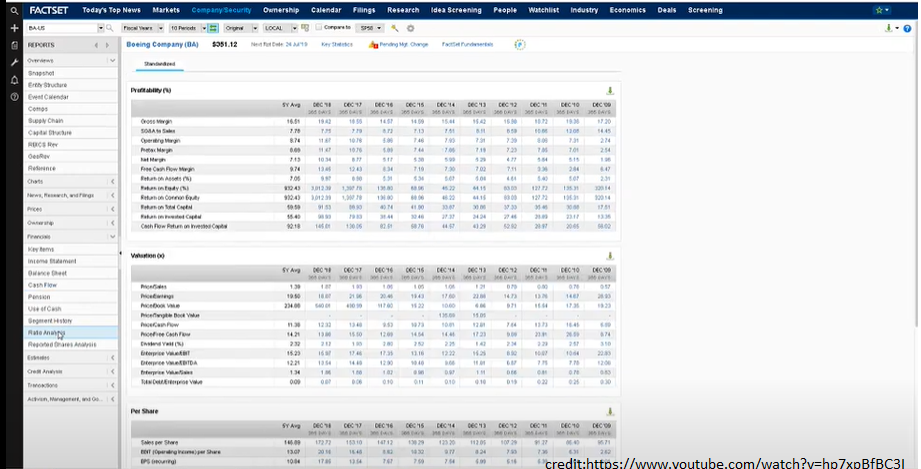

All that work you did in finding one company’s revenues? FactSet has it available, for all public companies:

Of course, the data stored is not always perfect [5]. However, for all the times you need something quick to reference, platforms that have already done all the work in an easily digestible format are invaluable. You don’t need to spend hours pulling data when it’s available with a few keystrokes. This convenience factor is one reason the platforms can charge a sticky subscriber base [6], though disruptors like Koyfin are trying to undercut them.

There are also companies like BamSEC and Last10K, which make finding the filings easier. For example, BamSEC will categorise different types of filings together, show titles for the filings, and allow you to quickly find previous editions of filings. These companies don’t have as much features as the platforms above, but still save time for an analyst.

Access to sellside research data

We’ve talked about the user experience, now let’s discuss the points about getting more data and paying for it.

Besides providing aggregated financial data on companies, the Bloomberg etc platforms also provide sellside research estimates.

As a reminder, these researchers are people at investment banks that publish reports on the company. These are usually the people being referenced when the news says “an analyst downgraded a company to a sell” or “banks raise the price target of a company.” Sellside research comes up with their own financial models with estimates for future company financials, supposedly using the model to come on a price target [7].

Many investors like to see these sellside numbers, in order to get an idea of where market consensus is. For example, if the mean of sellside estimates for next year’s revenue is $100, but you think it’ll be $1000, you’re either about to have a really good time or a really bad one.

If you’re a professional investor, you can always just email the banks to get their research [8]. If you really wanted to, you could compile all those pdfs and excels together, and do the benchmarking yourself.

Obviously no one really wants to do that [9], so the researchers provide this data to the platforms, who then show it to the investor community. If you want a quick summary of where sellside consensus is, that’s also available in a few keystrokes.

Access to company management

Many investors evaluate companies based on the quality of their management teams. To facilitate this, both companies and sellside research will host regular investor conferences. The intent for these is for management to meet investors, explain the company strategy to the new investors replacing all the ones who got fired, and to take questions.

Investors can update their financial models or view on the company based on these meetings with management. For example, if a management team had a poor response to your question, you might be interested in shorting the stock.

“Hang on, this sounds like insider trading”

Nope, it’s not. Would you think that Buffett’s annual shareholder conference, attracting 40k people yearly, is insider trading? If not, what makes the above conferences different? Just because you’re not invited to a party, doesn’t mean it’s illegal. There are rules governing what management can say, but this practice has been going on for a long time.

Industry experts

Investors are also interested in talking to employees in the sectors they’re researching. For example, if I’m trying to understand how Facebook advertising revenue might be, I’d want to talk to large buyers of Facebook ads. If they’re more optimistic about the product, that could be a positive signal.

Expert network firms like GLG, AlphaSights, Third Bridge exist to help investors find such people. These firms get paid to link investors up with industry experts; the consultants are also paid for their time. You’d be surprised how many ex C-suite people do such work in their spare time.

“Hang on, this sounds like insider trading”

Nope, it’s not. If you were interested in investing in a healthcare company, would you think that asking your doctor friends about the company is insider trading? If not, then why should the above be different? Just because you can’t afford the middleman, doesn’t mean it’s illegal [10].

Industry data

Lastly, investors are also using “alternative data” to better predict company results. For example, if you were interested in how well a mobile app was doing, you might be interested in the app download stats for that company. If you were interested in e-commerce sales, you might be interested in credit card data for an industry. If you wanted to monitor truck weights in order to estimate whether a company was doing more sales (heavier trucks), there’s a company for that [11].

There’s a large market of sellers for such data. Companies such as AppAnnie, SensorTower, QuestMobile are well known for providing app data. Companies such as Earnest research, Second Measure, are similarly known for providing credit card data.

“Hang on, this sounds like insider trading”

Would going out and counting customers at a store be illegal?

What this means for the retail investor

We’ve gone through both the public and private data that a typical fundamental investor might use. What does that mean for you as a retail investor?

If you believe that your investment advantage was having more information on the company than other people, you need to credibly believe that your research process was more exhaustive than the above. Alternatively, that your research process was different enough and using different sources that a typical professional might use.

Let’s walk through a few examples.

If you believe that your edge was a newspaper article citing how management was excited about a new product, you’d have to make the case that management wasn’t already discussing this with investors a long time ago.

If you believe that your edge was the app download data you saw on twitter, you’d have to make the case that investors didn’t already have access to that data before you did.

If you believe that your edge was that industry expert relative, you’d have to make the case that they know the sector better than the people the pros are talking to.

To be clear, all of the above scenarios could be true. Maybe management just changed their mind recently, investors saw but didn’t care about the app data, or the industry experts weren’t that expert after all.

My point here is not to say that it’s impossible, but that you should be aware of what the competition is, and what that implies on the advantage you need to have.

For example, if you found a small company that has a helpful dataset, but isn’t selling to investors yet, that might be a source of edge.

If you hired people to do manual grunt work by counting store traffic and taking pictures of receipts instead of relying on credit card data, that might be a source of edge.

If you did anonymous visits to company factories to see how busy they were, that might be a source of edge.

What you have to do is find the things that a normal pro would be reluctant to do. In a world where pros have access to more resources than you do, you need to look for advantages in the areas that are less desirable. Look at the chart below, and spot the gaps.

Footnotes

- I don’t have experience in a quant firm, so can’t speak to that personally. I do know quants pay for order flow though, and that’s likely included in the $30bn figure. Separately, note that an investment firm like a hedge fund is different from an investment bank; most investment analysts do compeletely different jobs than investment bankers. Sellside equity research is the role most similar to a hedge fund analyst, but researchers don’t actually invest money.

- Edge here refers to the relative advantage you have against your competition. We discussed why this was important in investing last month. Shoutout to Barak Paz for nudging me to write on this based on a convo we had.

- But usually not ask questions. Some rare companies let the public ask questions; most of the times the questions are coming from sellside research (not buyside investment analysts)

- It’s even worse if you’re pulling data from 8Ks rather than 10Q/Ks. Notice how there are no titles because the SEC likes seeing you suffer.

- A large part of investment banking is actually downloading the data and then making the adjustments needed to “accurately” reflect the company. Accurately here referring to whatever your boss feels like showing.

- This isn’t the only reason, though. Bloomberg has a sense of community, there’s a status signalling situation, and unlocking direct messaging is useful. Byrne Hobart goes more into detail on this here

- Whether they have a price target in mind and then adjust the numbers to fit, or the other way round, I’ll leave you to decide. Note that this critique can apply both to sellside and to buyside investors

- Retail investors are mostly out of luck here. You usually have to be a client of the bank and make trades through them in order for them to care. This gets into the business model of sellside research, which is out of scope for today.

- Unless you’re an investment banker who gets told to do so by your boss, in which case you spend days manually typing in numbers from a limited set of pdfs because your bank is restricted from other bank research. And then you have to manually adjust estimates because some sellside numbers are outdated or using incorrect assumptions. Yes, this happens all the time. Yes, it’s mostly a waste of time. Glamourous job, banking.

- This does have the potential to get more murky though. Black Edge, a book about the supposed insider trading at SAC, discusses the potential for abuse here. These chats are all supposed to be monitored by compliance. There have been occasions where the investor forms a “friendship” with the industry expert, and then starts asking for material non-public information.

- I can’t find the company off hand, though I know I’ve read about it somewhere. I think they were using camera data to image trucks and see how close they were to the road. The closer, the heavier, implying more sales.

If you liked this, sign up for my finance and tech newsletter: