Tell me why

Conviction level in this idea: 60%

Why do we believe in what we do? I’ve written previously how people don’t reflect enough on what they believe in, or not even know what beliefs they have. Supposing we’ve identified our core beliefs, what led to us developing and maintaining those beliefs? Is believing in the flying spaghetti monster different from believing in ice spikes on Jupiter’s moons?

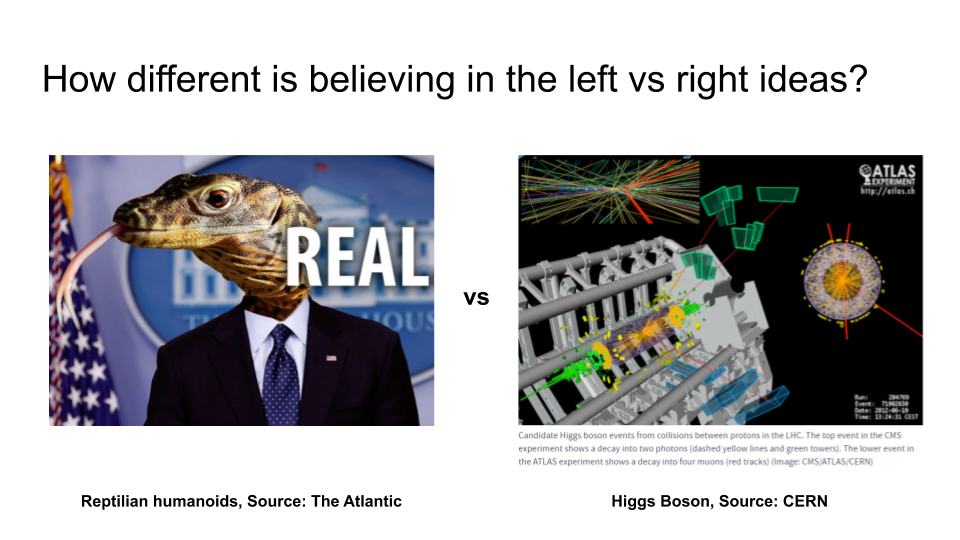

There are many “crazy” beliefs that the mainstream public would laugh at now. Flat earthers. Moon landing deniers. Shape-shifting lizard people. [1] Yet most people don’t think it’s crazy that 70% of Americans believe in some form of omnipotent being ruling over existence, nor that most people [2] think life involves some form of microscopic assembly line unzipping, squishing together, and re-zipping. What’s interesting to me too is how each faith will have ardent believers willing to defend their beliefs against heretics. Note here I’m using the word ‘faith’ liberally, across religion, science, philosophical, or other arenas. See how heated discussions can get about politics, religion, or the best bagel store in NY.

Why then, do we believe in the issues that form so much of our identity? I’m not sure if we have a good reason. For many, the environment in which they were brought up in determines most of their beliefs. There’s a correlation between having religious parents and becoming religious, some evidence that political views also transmit to children [3], and even a possibility your career choice might not really be your own. This is problematic if we’d rather live a life by our own choices and not by default. Unexamined life not worth living and all that.

Beliefs can also change over time, depending on how many people around you have a similar point of view, e.g. societal views on homosexuality. I’m curious as to how these changes come about, would like to learn more about this. There’s some evidence that ‘tipping points’ occur when ‘critical masses’ of people start to believe in the same narrative. If this is the case, are we simply subject to the whims of a small influencer group that sets our cultural norms and tells us why we want it that way?

At this point, some people will say that they’re the exception, that of course they’ve examined their life, that of course they don’t blindly follow the majority, and that they’re confident in their beliefs due to the evidence-based process they’ve adopted. Go Science! Some might quote Carl Sagan, saying, “Why would we commit belief when the evidence is so meager?” An evidence-based approach with bayesian inference frameworks seems like a good approach, where you continue to update your degree of confidence in an issue when faced with new evidence that proves or disproves your theory. I myself try to maintain my beliefs this way, which will be the subject of another post.

Yet there’s still a problematic issue if we choose the evidence-based approach. How do we evaluate the evidence that we encounter? The scientific crowd likes to extol the virtues of the scientific method, where you test and replicate results to make a point about how the world works. In other words, it’s the fact that a new discovery should replicate and generalise across a larger dataset that qualifies it to be scientifically rigorous. If I wanted to, I could theoretically verify how an electric circuit works, how I need food to survive, or how mixing acetylene and oxygen is not a good idea.

However, while some experiments are easily replicable, others are not. To some extent, we still have to take much of the science that we read on faith as well. When I read that “a new particle in the mass region around 125 GeV” was discovered in a huge science experiment involving colliding subatomic particles at high speed, and that this particle is fundamental to the universe, I have no option but to trust that it’s true. I’m never going to be able to replicate an experiment like that. It’s even unlikely for multiple replications of that experiment to occur elsewhere in the world. After all, how many similar particle accelerators will ever be built within our lifetime? I find this problematic, though I don’t know how to resolve it. My point here though, is not to discourage evidence-based thinking, but to point out we still seem to have to blindly trust something or someone. [4]

I guess… I want to believe?

If you like this, you’ll like my monthly finance and tech newsletter:

Footnotes:

- If you are really out there, know that I’m a proud supporter of the lizard kingdom should the time come for you to take over the world. Long live Queen Diplodocus and all that jazz.

- Couldn’t find a statistic on “number of people believing in DNA”, but did find this 2005 poll that claimed 80% of people found DNA evidence reliable. Newer articles all seem to refer back to this poll without doing a new poll, which I find disconcerting…

- As with nearly every social science paper these days, there seems to be concerns over replication for this. The alternative point of view seems to advocate that peer groups, particularly during college, have higher influence. Regardless, both are still part of the environment that you lived through.

- Cost of beliefs might also make a difference, as described in this tweet here. If cost is high and immediate, we have no choice but to believe it’s true e.g. running into something. If cost is low and delayed, we are free to believe in whatever we want e.g. the afterlife, how to save for retirement, how that last cookie doesn’t count towards your daily intake since it’s past midnight