Smartphones are boring, what’s next?

Takeaway

Now that the world is connected, what’s next? How will regulation handle tech?

Ben Evans on Tech in 2020

Ben Evans of the venture capital firm a16z did his annual presentation on tech recently. It’s similar in style to Mary Meeker’s internet trends annual report, though less lengthy or diverse. He talks about a few broad themes:

- Now that everyone is connected to the internet, what can we expect in areas such as ecommerce, entertainment, and other industries?

- What is the next tech trend, now that we’ve hit a plateau in smartphones?

- How will regulation evolve to deal with tech?

I’ll highlight key points below, Note that I might paraphrase for clarity.

We connected (almost) everyone. There are 5.5bn adults on earth, 5bn have a phone and 4bn have a smartphone

Some estimates show ~4.5bn people connected to the internet now, through a mix of phone and computers. Some of the countries that make the top 20 in terms of total connected users might be surprising: Nigeria, Bangladesh, Philippines combined have about the same number of internet users as the US, due to the large population size of the former group.

However, there’s a difference between everyone being connected to the internet, and everyone being connected to each other. We were sold on this vision that anyone would talk to anyone, but that’s not been the case. From immense isolations like China’s tech scene, to small segregations such as Quora being mainly users from India, we still live apart from each other [1].

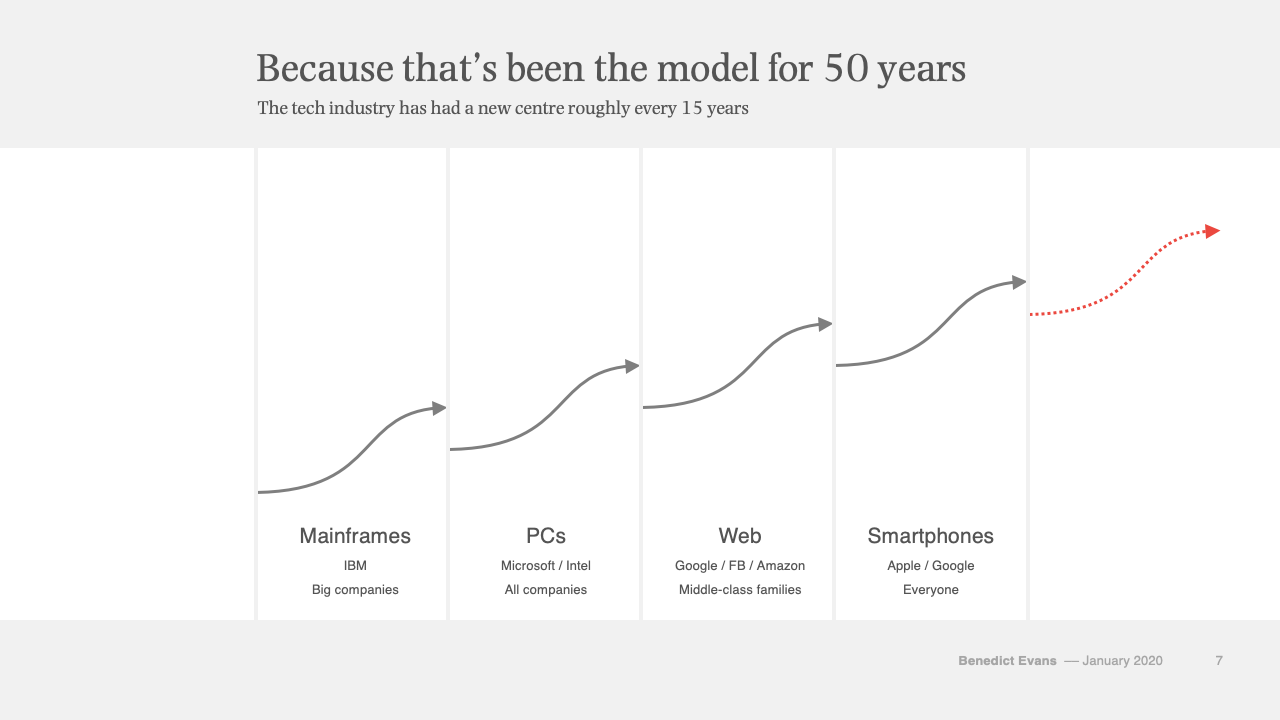

New technologies come in S Curves (from stupid to exciting to boring), and mobile has mostly reached the boring stage

For those unfamiliar, the S curve concept models how a technology’s life cycle is not linear. Instead, it follows an S shape, if the shape had been drawn by someone with as bad handwriting as I do:

Ben’s point is that mobile is no longer accelerating, and people have reset their expectations to a new level where mobile is the norm. Customer expectations are not static.

Ben discusses the impact that everyone being online will have on ecommerce, entertainment, and other industries. Let’s look at ecommerce first.

Ecommerce

ecommerce is big…But still ‘only’ 15% of addressable retail [2]

Notably, Ben’s “addressable” market excludes cars or restaurants, which have historically been offline experiences. That may no longer be the case, with internet sites and apps allowing car purchases or food delivery. You can even buy houses online now. This could mean that the addressable market for ecommerce is even larger.

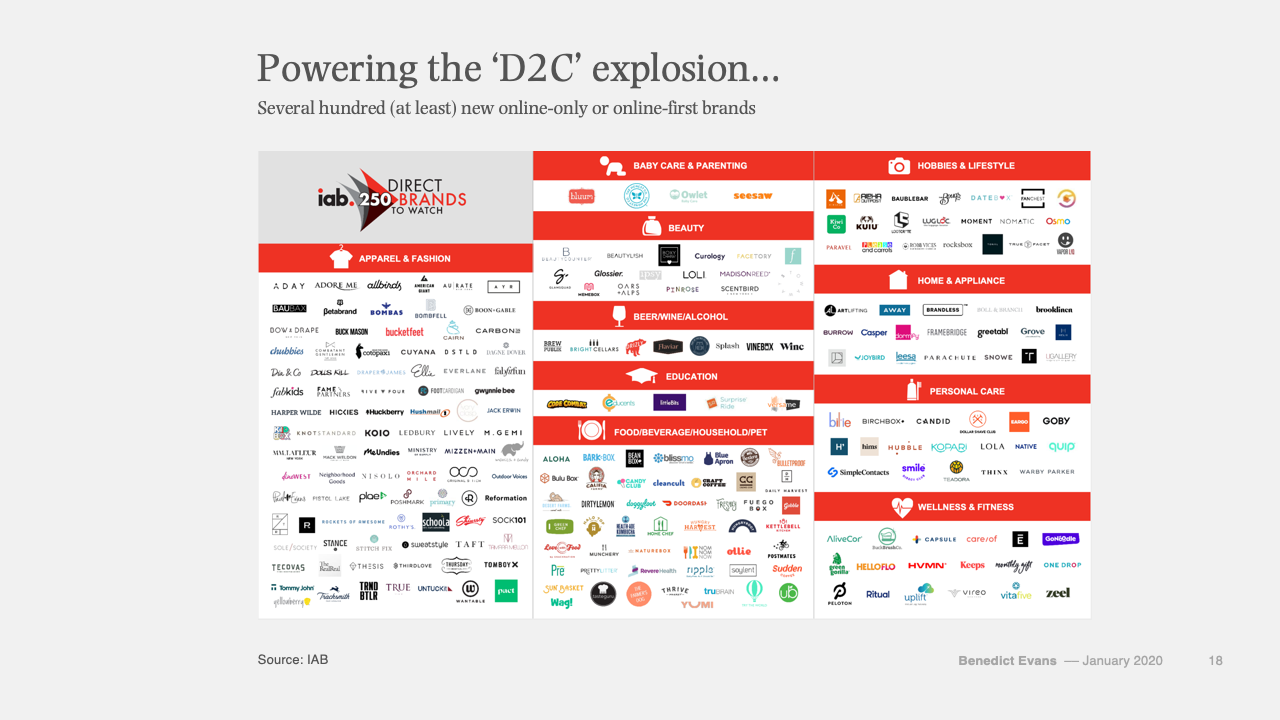

Independent ecommerce is now so big that the enabling platforms are worth tens of billions e.g. Shopify, Stripe

This trend has been a surprise to investors, which can be inferred by how the valuations of infrastructure companies such as Shopify (makes ecommerce easier) or Stripe (makes payments easier) have exploded over the past years [3]. We knew that there would be many people online. We didn’t realise how large a business opportunity it would be to provide a long tail of users with business services at a low cost.

Platforms for others are now a third of Amazon revenue

Amazon’s platforms here refer to Amazon Web Services (AWS) and the AMZN marketplace. AWS provides cloud computing. The AMZN marketplace is when AMZN acts as a 3rd party platform to let other merchants sell on the AMZN site [4]. Both of these business lines are now significant for AMZN, deriving value similarly from that long tail of users just discussed.

New retailing means new taxes e.g. AMZN product search, Booking/Expedia Google search

Stores pay rent to physically reach customers. When your store moves from the physical to the intangible internet, you pay a digital rent instead. Customer acquisition cost (CAC) is the new rent. This takes various forms, such as paying AMZN a fee to advertise your product, or buying ads on Google.

Ben also makes the point that this shift in rent isn’t new, and has happened whenever there’s a shift in business trends, for example Sears and its catalogues. The exception is when you can find a unique way to reach your customers directly without a middleman. Some investors thought that new Direct to Consumer (DTC) companies such as Casper (mattress company) were such an exception, but have been proven wrong on many.

Besides ecommerce, Ben also discusses TV and entertainment:

TV

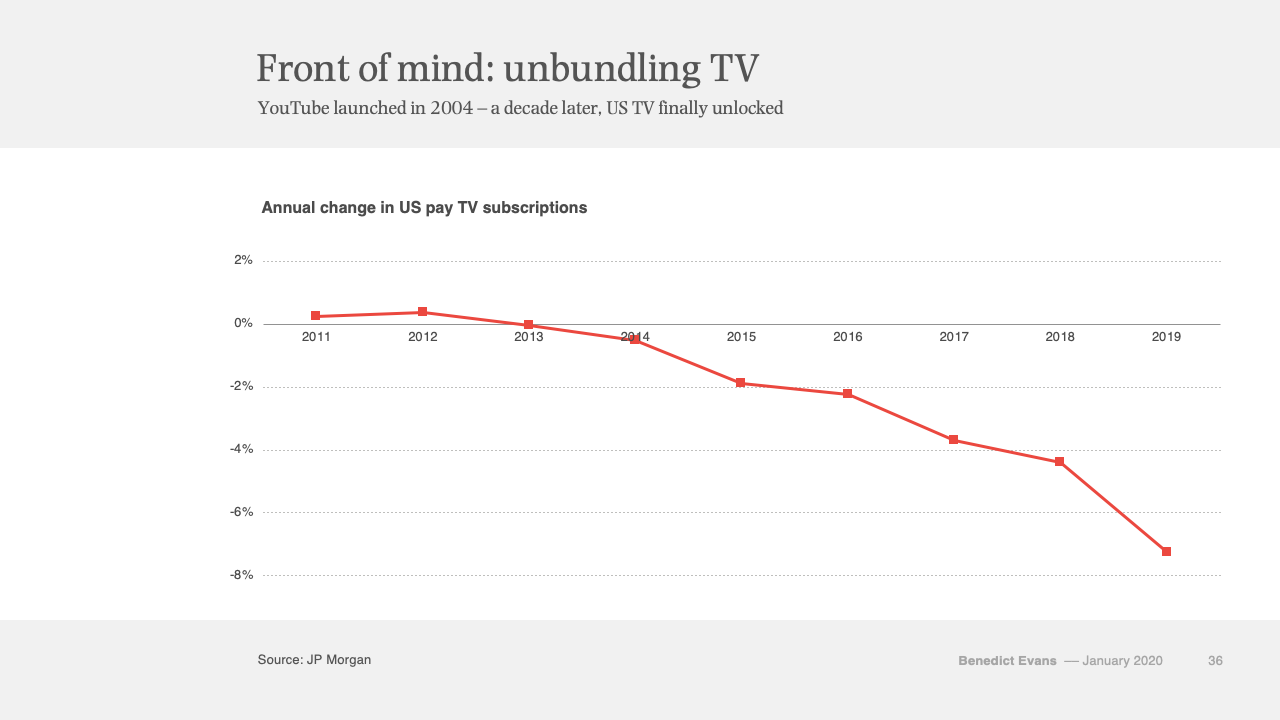

For generations, most of the US was sold a big and expensive pay TV bundle - this is now breaking apart.

Unbundling and Rebundling: There can only be so many brand relationships, Aggregators exist for a reason, Lots of rebundling coming

There’s a saying that business is all about bundling and unbundling, or packaging value together and then separating it into pieces. Ben believes that after this current wave of fragmented sales, companies will emerge to consolidate the sectors into oligopolies. I’m unsure what timing he has in mind for this. We’re still early on in the fragmentation for content, based on how many media companies have just started a video streaming service.

Took a decade from youtube’s founding, but pay TV subscribers have started declining. The change is happening faster than retail, and is most pronounced in teenagers

New forms of video are emerging, such as Twitch games live streaming

We haven’t stopped needing entertainment; we’ve just moved on to different channels. Despite that, the average person still watches 4 hours of TV, implying there’s way more time to lose for TV.

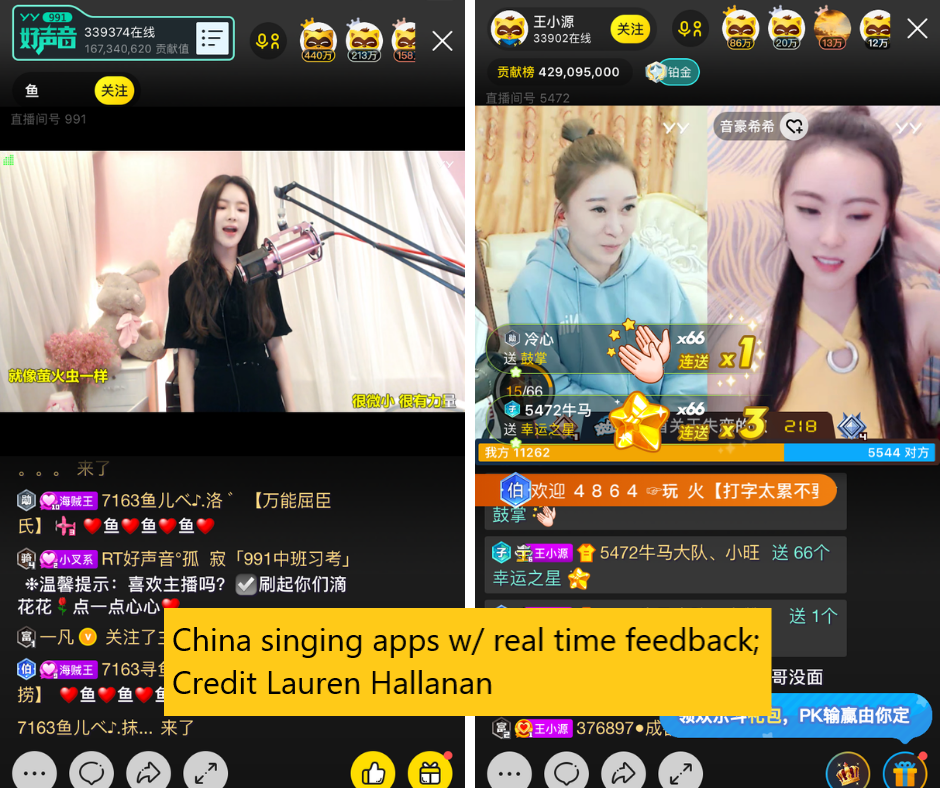

TV was one way and passive due to tech limitations with information speed. Newer forms of entertainment take advantage of the increased speed now by experimenting with two way, interactive formats. Hosts can now chat with their viewers directly, get their feedback on what they’d like to see, and even sell them merchandise.

Video game live streaming likely has huge room to grow, based on the increasing normalisation of gaming. 2mm people already watch the finals of a video games championship; how long before it catches up to the 17mm people that watch NFL?

Live streaming isn’t limited to games either, if you thought it was a niche hobby. The in real life (IRL) channels on Twitch have grown in popularity, and live entertainment apps in China such as karaoke are big. People now expect to be able to interact with the influencer and pretend they are close, perhaps having been conditioned with the rise of social media and loss of space. A celeb shoutout app like Cameo is one of the fastest growing marketplaces this year.

Lastly, Ben discusses how tech is also coming for narrow segments of the economy [5], and that VC investment has now grown beyond just being a US phenomenon.

Which brings us to: What’s next?

The next S curves

The tech industry has had a new centre roughly every 15 years e.g. mainframes to PCs to web to mobile. What’s next?

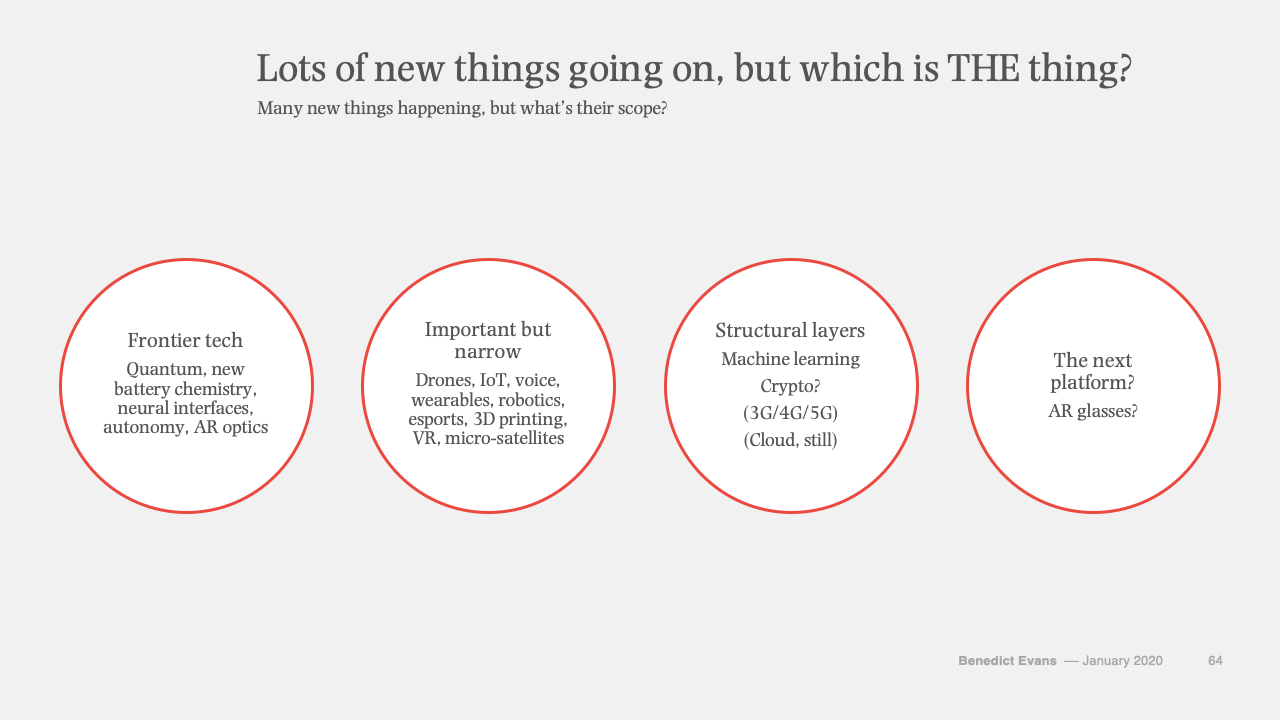

New things such as machine learning, crypto, AR are happening, but that’s not the only focus for 2020s

Ben lists many areas of new tech. The concern isn’t whether the tech will grow, but whether the tech will grow to the scale that mobile, PC, mainframes have in the past. He’s doubtful that VR will be the next big thing.

I’m more (irrationally) optimistic on VR, and hope that the clunkiness of experiences today will evolve to an immersive, lifelike entertainment hub. Just as Palm Pilots were stepping stones on the way to mobile, current VR setups will be replaced by cooler toys.

Ben then covers regulation’s return:

Regulation

Regulation is the next big thing coming to tech

From being an applauded boy genius in 2008 to being deemed a robot in 2019, examples such as Mark and Facebook indicate that opinions have shifted on tech. Legislation usually lags public opinion, and we’re seeing politicians go after tech companies now to stay relevant [6].

Complex questions seem to have simple answers that don’t stand up to scrutiny

There are always tradeoffs in regulation. e.g. “There’s bad stuff on your platform – take it down”

Ben believes that we do face complex problems, just as we have for years. Solving these problems with simple soundbites is not likely to work. I’m inclined to agree, as discussed later below. However, I’m less optimistic that regulators will agree here. They’re incentivised to regulate, and we’re likely to continue seeing increases in ineffective regulation in upcoming years.

Coverage of real issues also seems more focused on creating moral panic

I’m not sure this is new. Media has always been incentivised to get the largest audience possible. We’ve been searching for scandals ever since we could spread stories about each other.

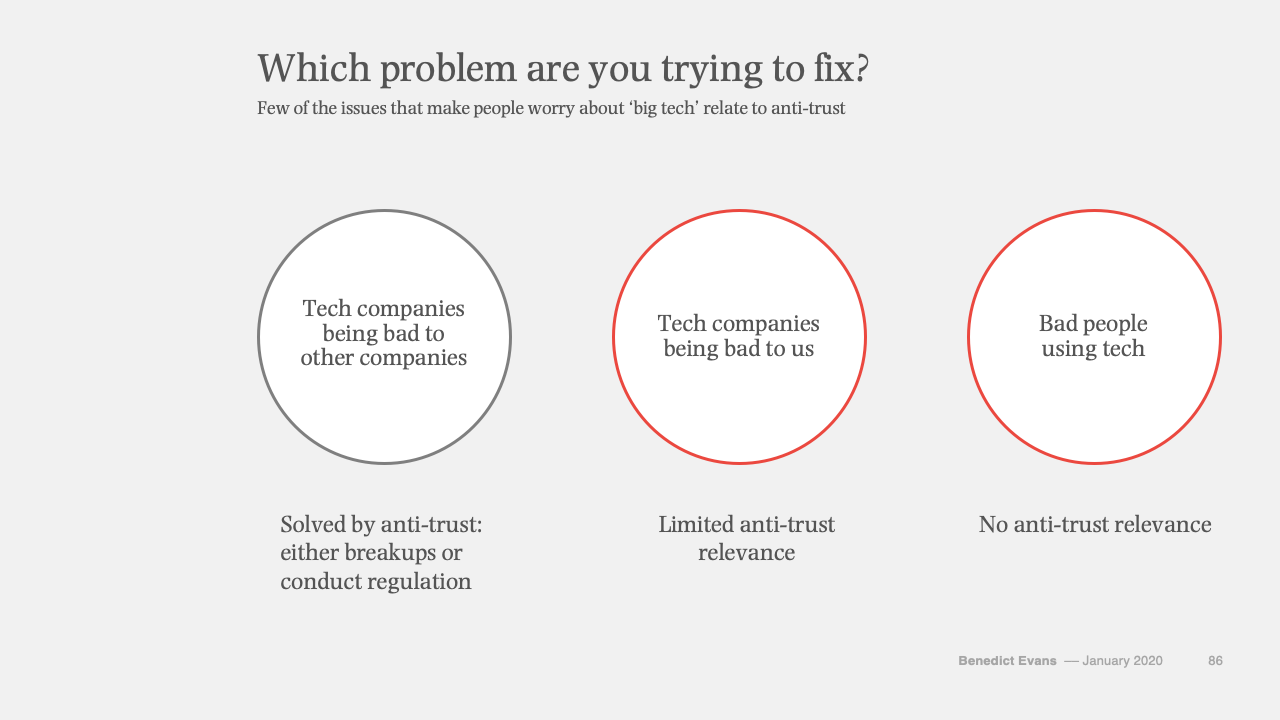

Few of the issues that make people worry about ‘big tech’ relate to anti-trust

Ben’s skeptical of anti-trust; Stratechery also wrote about the possible negative impacts. I’ve read varied accounts on the effectiveness of anti-trust regulation, and haven’t made up my mind yet on where to land on this issue. I’d likely lean away from regulation though, as implied above.

Lastly, Ben discusses the global nature of tech:

Global tech

China and India internet usage is now bigger than the US

Interestingly though, we’re still not interacting much with each other. China’s users are largely walled off, and US sites have remained US centric. For example, everyone on reddit (top 20 visited site globally) still assumes everyone else there is from the US.

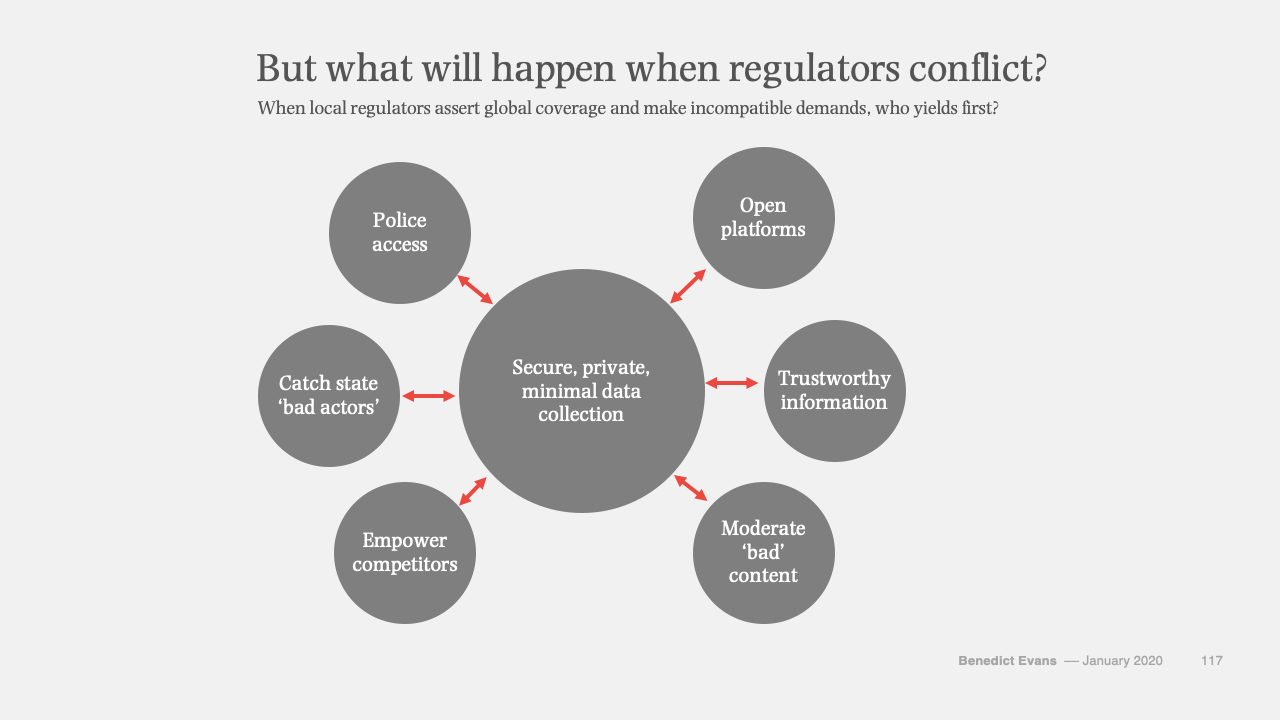

We’re seeing a clash of different country regulations

Tech has become part of the world, so it gets regulated as part of the world

Given the fragmentation, how then should countries regulate tech companies, who are now more global than companies in the past? We’re still figuring things out, and companies might cater to the strictest regulation in order to be on the safer side. That likely worsens the user experience for everyone. If you’ve noticed more annoying popups related to cookies in the past year, that happened due to regulation.

The only certainty: regulation as a regressive tax. Much of regulation is a fixed cost that affects new entrants disproportionately

Many regulations have good intentions. GDPR in Europe is intended to protect privacy, AB5 in California is intended to protect worker’s rights, Dodd-Frank to protect the financial system.

One problem with regulation though is that complying with regulation costs money. And between a small business and a large one, you can expect the large business to be better placed to afford the legal costs required. Hence an increase in regulation usually helps large incumbents and hinders new entrants. For example, Facebook and Google grew share in Europe post GDPR passing there, since all their competitors started dying out.

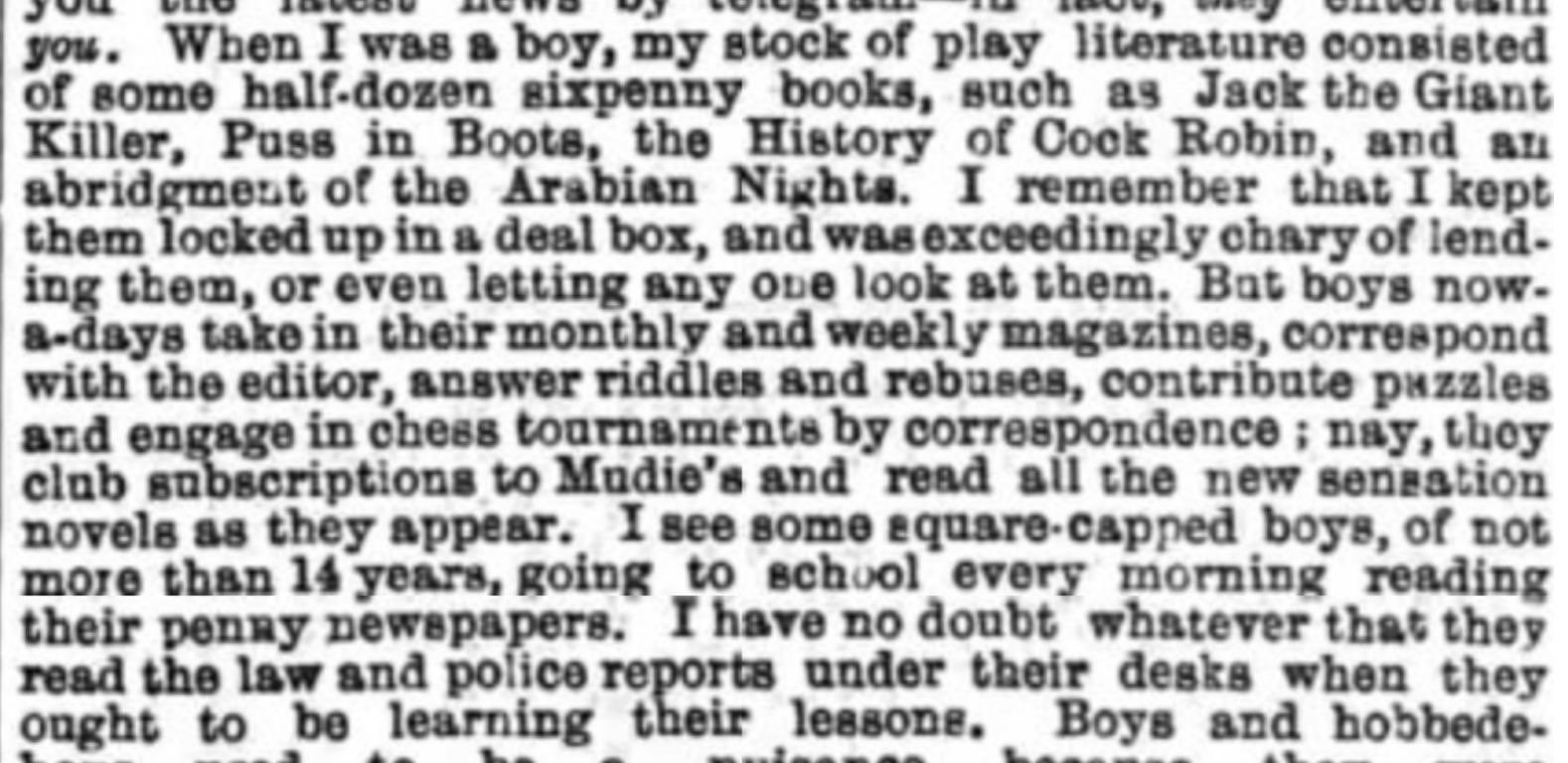

Worrying about tech isn’t new

Every wave of tech changes the world, and gets regulated

The twitter account Pessimists Archive has a collection of newspaper clippings showing historical opinions about tech which show this to be true. For example, here’s people complaining about newspapers:

However, I don’t think this means we should adopt the opposite stance, and not worry about tech at all. Like any change, there’s likely positive and negative aspects. Regulation should be adopted after carefully studying where tech is failing us, and it won’t be easy to get right. The first step in doing so is getting more educated about tech.

To summarise, Ben took a closer look at how tech has impacted ecommerce and TV, and thought about what could come next. He then highlighted the incoming pressure of regulation, and the globalisation of tech’s influence. Worries will always exist, legislators will try to regulate, and businesses will find ways around them.

Some things change, some things stay the same.

Footnotes

- Think about how many internet friends you have from China, India, Indonesia, or Brazil (if not your home country), which have the 4 largest internet users outside of the US.

- Addressable retail = ex. cars, car parts, gasoline, restaurants & bars

- The Masters of Scale podcast recently covered Shopify’s rise and how it went unnoticed for a long time

- This is in contrast to being a first party merchant, when AMZN is the one buying and reselling the items. 3rd party marketplace value of goods sold (GMV) is now larger than 1st party sales, though the revenue to AMZN is still lower.

- e.g. RigUp for oil field workers, Honor for elderly care, Incredible Health for nursing

- I wonder how much of it is stated preference (what people say) vs expressed preference (what people do). For all the people complaining about facebook and others, their user base is still tremendous.

If you liked this, sign up for my monthly finance and tech newsletter: