You don’t want quality time, you want garbage time

Takeaways

- You don’t need fancy tech to do many things, and usually business needs dictate, not tech

- Robots are coming for sellside equity research and it might not matter

- You can’t get quality time by chasing after it

Question of the month

What is something you wish you’d done later in life, rather than earlier? Reply directly to this email to let me know!

Robots vs people, tech stacks

If you’ve been curious about the hype on machine learning, Vicki Boykis wrote a couple of posts that provide context to the hype. Vicki is a data scientist in machine learning, and her newsletter’s main theme is “you don’t need this fancy tech to do x, y, and z, and usually the business dictates, not the tech.” Her posts give an overview of machine learning, and cite WeWork and Netflix as examples supporting her theme. Highlights below:

Most startups (and big companies) don’t need the tech stack they have

The tech stack is the set of software that companies use to build whatever they’re selling. It includes things used to write code, decide on code, and deploy it. Vicki’s point here is that most companies don’t need all the fancy tech applications they are currently using, and there are simpler but less sexy alternatives.

That includes “machine learning,” which she defines as:

a systematized, automated way to take raw data, transform it, run a model on it, and show some sort of results that lead to decision-making

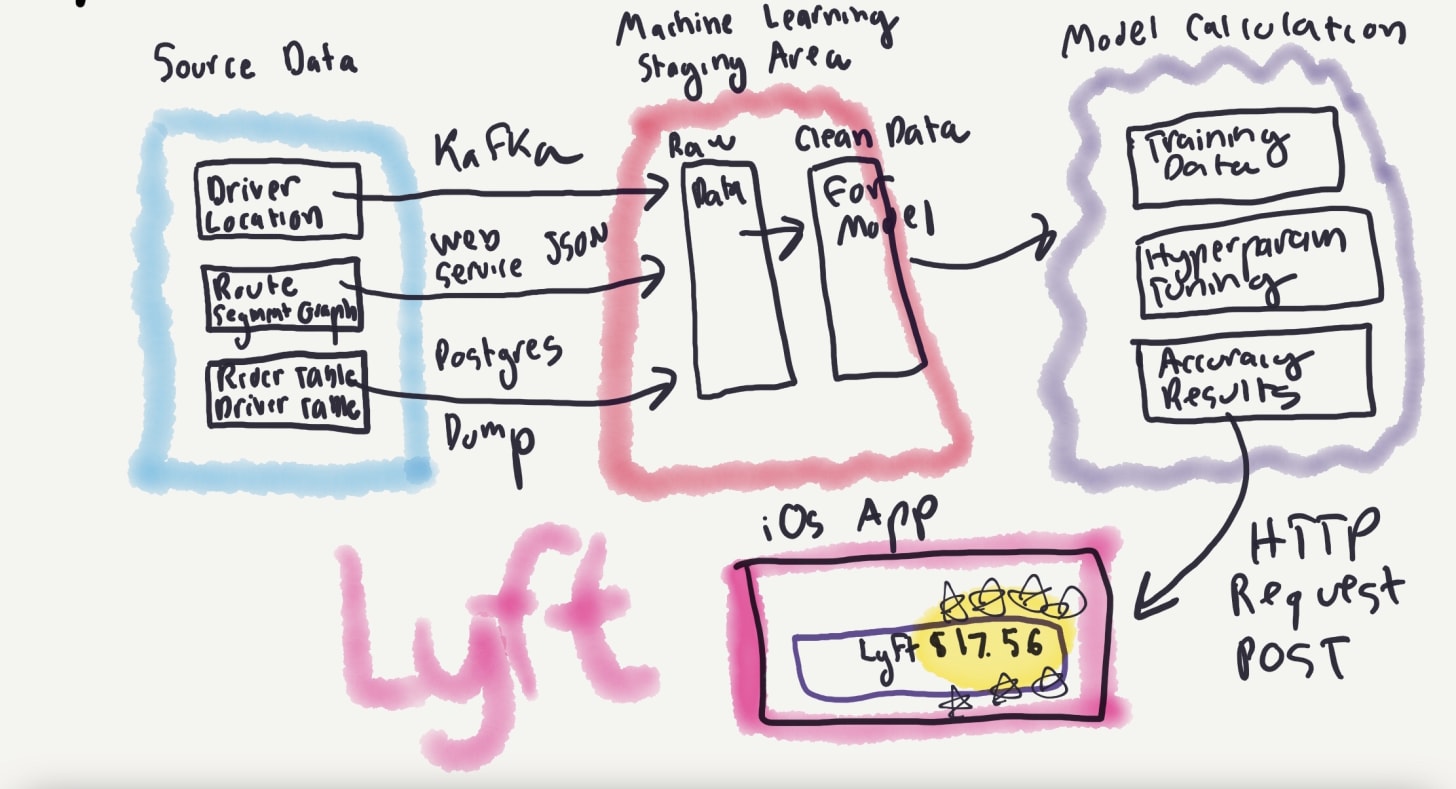

Companies that provide personalised content, such as Netflix, Facebook, or Amazon use machine learning to do so. What does this look like in practice? She walks through how Lyft might calculate trip prices:

At a high level, there seem to be three stages involved:

- collecting data from various sources

- moving it to an intermediate staging area, and cleaning the data format

- using the data in a statistical model to calculate a result [1]

People focus on the sexiness of the third stage, but stages one and two cause most of the problems and are where data scientists spend more of their time. These problems include:

First, your data sources might start producing incorrect data. Or, the data might be dirty: for example, what if your system has Philadelphia as Phla, or Phila, or Philly?

Then, you might get something called model drift [where predictive ability decays over time.] Or, you might have incorrect model feedback loops […] Or, perhaps the model is the wrong one for the shape of the data

Then, on top of the data issues there are your garden variety software engineering issues: data not getting ingested quickly enough, data feeds breaking, data incompatibility issues between formats etc

What does this mean if you’re a company looking to use machine learning?

first, don’t believe the hype that any one single machine learning platform will solve your needs

[second,] make sure that if you or your company has or is thinking about [using machine learning], that it’s very carefully monitored, tagged, and that results are constantly evaluated, and that it has tests

And what if you’re a consumer and interacting with recommendations from machine learning?

if you’re a consumer, think about all the stuff that has to happen for a recommendation or action to make its way to you, and be skeptical. The system is not always right. We are still very much in the early, experimental days

No wonder I haven’t matched with Sharon Stone yet.

Vicki then cites WeWork and Netflix as cases where **the tech wasn’t needed or would be overridden by business needs. **

Wework didn’t need Kafka [2], a complex distributed software that coordinates data transfer. Vicki does some calculations showing why a simpler software would have worked for what WeWork wanted to solve then, and concludes:

The overhead in setting up [the complex distributed system vs the simpler database] is enormous, because distributed systems are hard - really hard - and much, much harder than traditional systems

Overarchitecture is real […] Using these tech stacks leads companies to take on unnecessary debt, which leads them to have to seek out even more money in the VC cycles instead of running lean and weaning themselves off other peoples’ money

Given the downside of increased complexity, why do people internally keep pushing for more complicated systems? Vicki believes it’s a matter of incentive alignment on the developer end:

While many use cases don’t require Kafka, it’s an easy tool for developers to recommend it so they can both work on it and talk about it later. It’s not always obvious to even developers themselves - sometimes they like working on shiny things out of the best intentions

Besides times where more complex tech isn’t needed, there are times where tech is overridden by business needs. Netflix’s machine learning recommendation algorithm has become less relevant over time:

The niche, discerning customers that initially came to Netflix to seek out custom-tailored recommendations in those famous niche categories (“Steamy British Independent Dramas”, anyone?) become under-served as mainstream content that’s less risky pushes them out of the way

What happens when tech and content fight at a company who is quickly becoming a dominant force in content purchases and production, rather than the tech that got them there? [The recommendation system] becomes more irrelevant.

If the recommender system recommends content that the business doesn’t like, and the business is driving the bus, the business always wins

In this case, the use of machine learning to give niche recommendations becomes less relevant over time, as Netflix moves to cater to the general audience. I’d say Vicki was prescient on this trend, given Netflix’s announcement of a top 10 row in your feed, which doesn’t require any sophisticated recommendation algorithm. Move over machine learning, the Count is here to steal your jobs.

We’ve seen a general overview of how machine learning works, the problems that can occur along the way, and what that implies for both companies and individuals. You likely don’t need all the fancy tech you’re building, and will frequently overrule it due to business considerations.

Robots vs people, sellside equity research

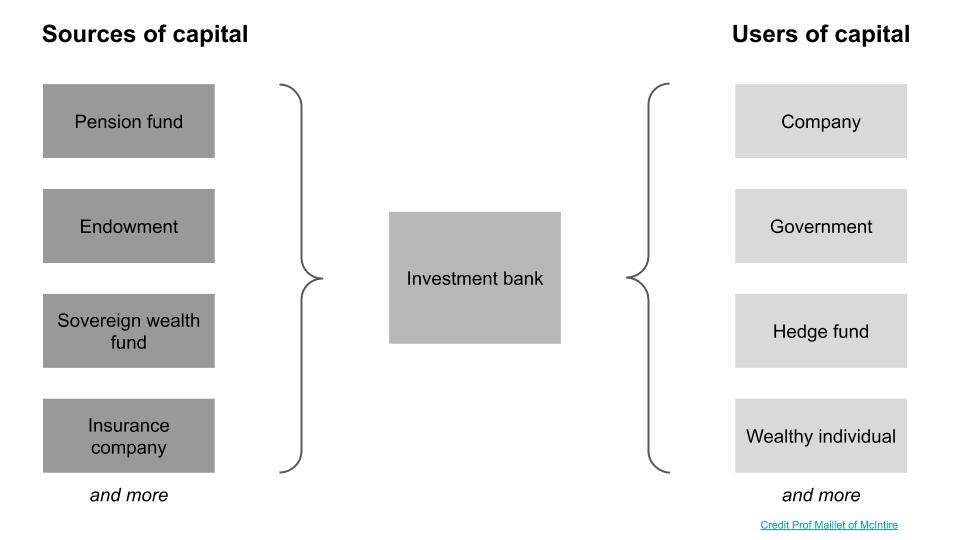

If you think of finance as an interaction between sources of capital and users of capital, investment banks such as Goldman, Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan sit in the middle, facilitating transactions between those who have money and those who need it.

Banks have bankers that cover a specific financial product (equity, debt, M&A etc) or a specific industry (consumer, healthcare, tech etc) and arrange for corporate finance transactions within their coverage area.

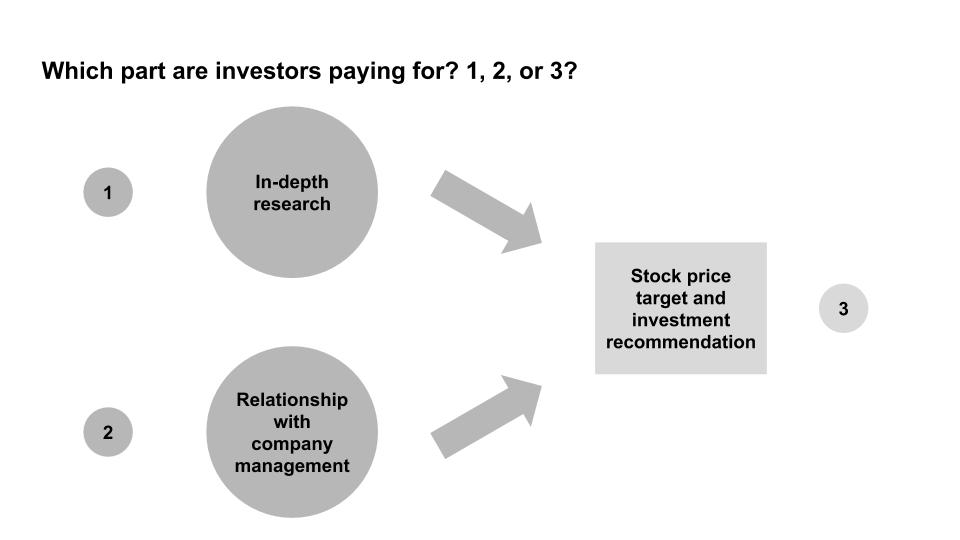

Outside of these transactions, banks usually have an equity research group, which issues views on stocks based on researching the company and maintaining a relationship with company management. These are the “buy/hold/sell” recommendations or price targets you see reported in the news. Note that these are recommendations, and the research group doesn’t take a position in the company, which distinguishes them from professional investors [3].

Equity research is sold to professional investors, who then theoretically use that information to make investment decisions. These investors do their own research as well though, so it’s uncertain how much they incorporate from bank research. Importantly, they do not pay equity research based on the accuracy of the recommendations, instead doing so indirectly via trading commissions through the bank.

Hence, it’s an open question as to what the investors are paying for: 1) the research, 2) the relationship with the company, or 3) the investment recommendation [4]. My sellside (research) friends would argue it’s all of them, my buyside (investor) friends would likely say it’s (2), and my retail investor friends would likely say it’s (3) since they aren’t provided (1) and (2).

If you assume that the largest value add comes from (3), this paper by Braiden Coleman, Kenneth Merkley, Joseph Pacelli on computer programmed equity research would be interesting. They study how “Robo-Analysts,” human-analyst-assisted computer programs conducting automated research analysis, perform against human research analysts by analysing the differences in recommendations from both.

The team identified firms that used robos, collected stock recommendations from them [5], and then test three hypotheses around bias, frequency, and outperformance. They find results consistent with all three, and we’ll look at them in turn:

First, Robo-Analysts collectively produce a more balanced distribution of buy, hold, and sell recommendations than do human analysts, consistent with them being less subject to behavioral biases and conflicts of interest

The first is saying that robos have less bias than human analysts, who also have conflicts of interests. As a result, robots recommend stocks with a more “natural” distribution in recommendations and are not all “buys” with no “sells”. These conflicts of interest are “related to economic incentives such as obtaining investment banking business or currying favor with management.”

Sarbanes-Oxley was intended to reduce such conflicts of interest, by limiting contact between the investment bankers (financial transactions) and the equity research group [6]. Even if you assume that it’s successfully limited contact, there’s still an incentive to publish positive reports of companies for the analyst. If you’re a CEO and have a “buy” rating and a “sell” rating on your stock from different analysts, who are you more likely to be friendly with?

Second, […] Robo-Analysts revise their recommendations more frequently than human analysts and also adopt different production processes

The second is saying that robos update their inputs more often and with different data than humans, and hence update their recommendations more often. To understand this, we need to understand how companies release financial information. In the US, companies release one large annual report (10K) and three smaller quarterly reports (10Q). In addition to that, they do earnings announcements ahead of these reports (8K) which contain their quarterly results and could include additional information.

Investors usually trade on 8Ks, since that information comes ahead of the 10Q. Likewise, human analysts also update their reports in response to 8Ks. The robos though pay more attention to the 10Q and 10Ks, and are more likely to update after those filings.

Whether this second finding is interesting depends on what kind of investor you are. Many investors trade around earnings announcements (8K). Since half of investing is an expectations game, and most of the info these investors want to know is in 8Ks already, getting fewer recommendations after 8Ks and more after 10Qs is less helpful. You’d want to know as soon as possible rather than wait for the more detailed 10Qs to be out, since the price moves in response to 8Ks.

Third, […] portfolios formed based on the buy recommendations of Robo-Analysts appear to outperform those of human analysts, suggesting that their buy calls are more profitable

The third finding is the “so what” of the paper, stating that the above two findings matter because you get better returns when following robos than human analysts. This happens for “buy” recommendations but not for “sell”, and they believe it’s because humans are less likely to downgrade “buys” and the robos are overcorrecting and issuing too many “sells”.

I have one quibble with their methodology, which I’ll put in the footnote [7]. Overall though, if you believe that stock recommendations are important, as many retail investors seem to, this paper makes the case that you should be following robo analysts as well, since they’re less biased, update more frequently, and could add outperformance.

What that implies for the equity research industry depends on where you believe their value add for the buyers of their service is. If it’s (1) or (3), this paper is bad news, but less so if it’s (2). I’m 60% confident we’ll see an increase in robos, and that still won’t matter for most research analysts.

About quality time

About Time is one of my favourite movies ever, and not just because it features Rachel McAdams in yet another time travel movie [8]. One of the messages it bludgeons your head with at the end of the movie is to treasure every moment of life. Which, despite coming from a rom-com, is actually an important takeaway I believe in.

If we should treasure every moment, what about the concept of quality time then? Ryan Holiday recently wrote about how he disagrees with the concept entirely:

It’s one of those lines we throw out casually: “I want to spend more ‘quality time’”

The perfectionist side of our brain […] wants everything to be special, to be “right.” But that’s an ideal that [we] can’t always live up to

The result? An inevitable sense of disappointment

The reason is that there is no such thing as “quality time.”

Quality time is a concept that has been around a while, with interest in it growing over time.

It’s even one of the love languages.

Does this mean we’ve been living in a collective delusion, trying to chase something that doesn’t exist? Ryan thinks so, quoting Jerry Seinfeld:

“I’m a believer in the ordinary and the mundane. These guys that talk about ‘quality time’ — I always find that a little sad when they say, ‘We have quality time.’ I don’t want quality time. I want the garbage time. That’s what I like.”

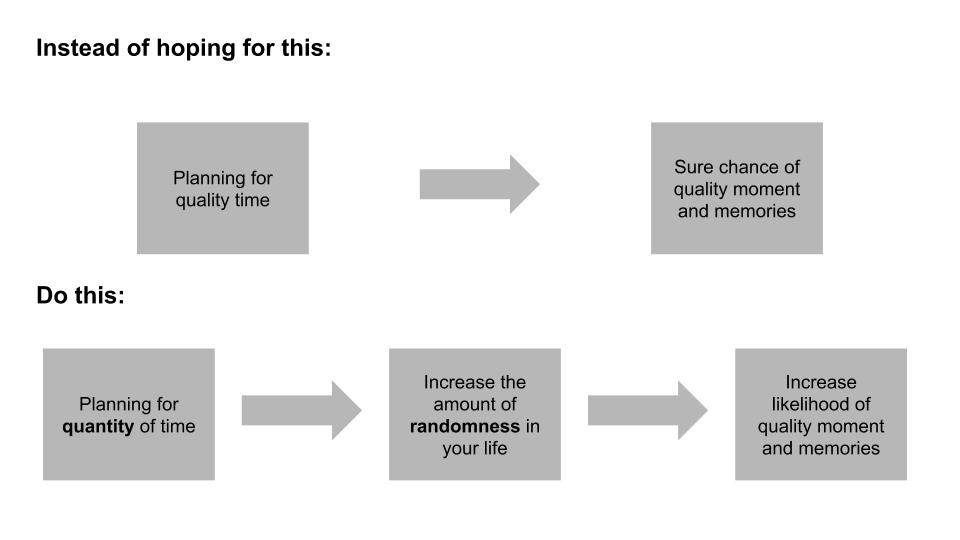

I mostly agree with Ryan and Seinfeld. Time spent can be high quality, but chasing quality time itself is fruitless. This is due to a combination of 1) expectations and 2) randomness.

We desire quality moments and to make quality memories. It’s tempting to think that we can create quality time just by designating it so, such as via a vacation. That generally ends up backfiring due to our raised expectations being let down by reality. If we expect that our vacation is going to be perfect, any single mistake ruins the experience.

In contrast, you are likely to get a positive surprise when you have low expectations, which is likely the case during a “normal day”. It’s hard to match perfection, and easy to beat normal. Because of this, it’s more likely quality moments come out of chance.

If you can’t engineer quality time, and it’s more a matter of random events, it follows that you want to increase how often such events happen. You can’t increase the probability, but you can increase the duration for such events to occur. Put another way, you want to increase quantity of time, and not engineer quality time.

Ryan indirectly implies that duration is the key, by quoting another advisor on how to find that ordinary time:

“You have to find the moments between moments.”

Sometimes these awkward, in-between moments allow for conversations that never would have happened otherwise. Even some of my best writing and thinking have come when I was stuck somewhere I didn’t want to be, or doing something I didn’t want to do.

When you’re out of excuses for being busy […] you’re forced to just make do with what’s in front of you

You want as much time as possible with your loved ones, since that allows more opportunity for randomness to create situations that become memorable moments. If you’re not making the time for chance to happen, it’s more difficult to get that quality relationship you’re looking for. You don’t need quality time, you just need time.

Sometimes you can’t find what you want by looking for it.

Shoutouts

- A friend at a NYC VC firm is looking to hire an Associate/Senior Associate; email me for details

- This person will be primarily focused on driving evaluation of new firm investments, developing investment theses, and sourcing new deal opportunities

- Career track role, with the goal being to develop the entire venture/growth investing skillset

- Typically this role is good for those looking to continue or enter an investment career, start companies, run growth- stage businesses (e.g., CFO, COO), or attend top graduate schools

- After 5 yrs with Deloitte and 3 yrs running Tail Risk, a cybersecurity services provider, Rob Terrin realised that he couldn’t solve the cybersecurity talent shortage alone. He’s launched BlueTeam, a cybersecurity talent marketplace to connect independent contractors with companies that need help

- I spoke with Ben Simpson of Fixers, “the best platform for running a travel or experience business.” Think Shopify but for travel and experiences

Other

- Is the momentum factor in stocks explained by randomness?

- The 4 major parts of shipping and maintaining a software application, and the products, methods, and services developers use [9]

- Buying your way into nobility

- “Romeo and Juliet is not a love story. It is a six-day relationship between adolescents and an infatuation that leads to a tribal war.”

- Interactive documentary of Jheronimus Bosch’s artwork “the Garden of Earthly Delights”

Footnotes

- Vicki’s a bit light on explaining how the machine learning model is generated, saying “That dataset is plugged into a working statistical model, which trains and picks the most important features (the variables that make price go up or down), tunes hyperparameters (the metadata about the model, such as how many times you want to run it), and, as a prediction, spits out the number”. My understanding so far of models is that people end up using some multi linear regression. And if they want to get really fancy, they use multivariate non linear regressions.

- Alright, WeWork didn’t need many things, but let’s focus on the tech side for now

- Depending on the firm’s compliance policy, the equity research analyst themselves could have a position, but that’s extremely unlikely and I think might actually be banned. Confusingly, the bank as a whole could and likely does have a position through their asset management group, which is a separate line of business from equity research.

- With new regulation from MiFID, the incentive structure for equity research is also changing, resulting in changes in behaviour from banks. Also, I’m not making the case that equity research analysts are bad at their job; some people such as Mary Meeker got their claim to fame due to good work as a research analyst

- They focused on recommendations “because they are the most commonly reported output across Robo-Analyst firms, and also represent the output that retail investors focus most on”

- It also included rules such as requiring “research reports include price charts that track the price movements of the stock over a historical period relative to the analyst’s recommendation”. Having removed those pages when compiling materials for company management when I was in banking, and not paying attention to them on the buyside, I wonder how effective well-intentioned regulation actually was

- They construct the portfolio by “add these stocks to the relevant portfolio at the close of the following day’s trading” after the recommendation was issued. In other words, the robo issues a recommendation, there’s a trading day, and then they put the stock in at the close. Wouldn’t the price already have been affected by the recommendation? If not, I wonder how much is a momentum or randomness factor despite them already using a Fama-French factor model

- Yes, I know it received mixed critical reviews. Fight me. Rachel was also in Time Traveller’s Wife (meh) and Midnight in Paris (great, and not to be confused with an American in Paris, if not you’ll watch half the movie wondering when the musical bit is supposed to come on. Not that it happened to me of course)

- h/t Caitlin Bolnick

If you liked this, you’ll like my monthly newsletter. Sign up here: