Are we as gullible now as we used to be

Takeaway

Historical accounts are often exaggerated; we seem to be as gullible then as we are now.

Are we as gullible now as we used to be?

Andrew Odlyzko looked into a famous financial bubble and argues that we haven’t changed much in terms of how gullible we are. He describes a famous exaggerated anecdote, the source of the exaggeration, and then a likely original source of the tale.

One of the most famous [apocryphal] anecdotes in finance is of a promoter in the 1720 South Sea Bubble who lured investors into putting money into “an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.” [Other tales then] all reflect the high level of credulity displayed by the investors of 1720. However, it is debatable whether their gullibility was greater than that of the most sophisticated investment professionals in recent times

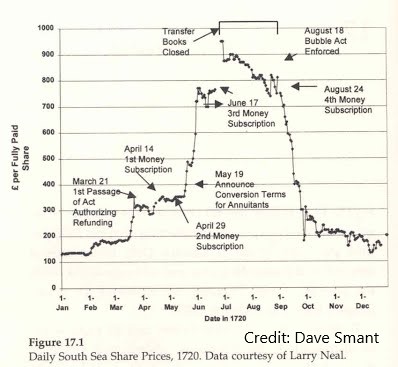

The South Sea Bubble is a time period surrounding the famous financial bubble in the stock price of the South Sea Company, which looked something like the below.

Andrew traces the origin of the anecdote above to a book by Oldmixon [1]. The full anecdote is too lengthy to copy directly so I’ve placed it in this footnote [2], and the summary is essentially:

A guy was raising money for ‘A company for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.’ He wanted to raise 5k shares at $100 each. To buy the shares you could pay a deposit of $2, with the remainder $98 to be paid when the full details were announced in a month. Within a day he had gotten offers for 1k shares, and he disappeared with the $2k he raised.

Andrew’s point is that even in this embellished anecdote, the guy did say he’d provide details in a month, which isn’t that different from how investments are made these days. He’s got a point. VCs at early stages invest in the founder and not the idea. SPACs are vehicles for investors to back another team doing a buyout. To pay to play, with the promise that more information about the idea is coming, is less crazy than it seems

Based on GDP per capita […] the gains reaped by the projector are comparable to about £2 million […] That is not shabby. But it pales when compared to the sums collected by promoters of the innumerable ICOs (initial coin offerings) in the last few years

I think the general point is true, though I’d quibble that the amount of investors that could invest in ICOs is far larger than that who could have invested in the offering, and that’s leading the difference. Apparently ICOS raised $8bn in 2018

The South Sea Bubble was largely inspired by John Law’s Mississippi Scheme in Paris, which reached its peak at the end of 1719. Both the French and the British manias were enabled by the return to relative peace and tranquillity after several prolonged and debilitating wars. Interest rates were dropping, and investors’ “animal spirits” were stirring

This sounds similar to George Soros’ view on reflexivity or Howard Marks’ on cycles.

Andrew goes on to describe what he thinks is the likely actual origin story of the famous anecdote. Again, it’s too lengthy to copy, so I’ll relegate to a footnote [3] and summarise here:

A paper ran an ad for ppl to buy rights to subscribe to the eventual share offering ‘for a new insurance company to be proposed, (whereof publick notice will speedily be given in this paper)’. The rights cost $0.05. After a few days the paper ran another ad saying this was a hoax meant to show how easy it was to deceive people.

Andrew points out how $0.05 even then was not a huge amount of money, that the total amount raised was low, and also that since the insurance industry was new then it might be less crazy than you think to invest blindly.

At the peak of a mania, it is often difficult to tell the difference between satire and reality. As just one example from our era, consider WeWork’s stated mission to “elevate the world’s consciousness.” Several compilations of South Sea Bubble projects list three for building or emptying toilets. Carswell in his book says ads for those ventures were “inserted as pure jokes, which have imposed only on historians”. But they may not have been jokes, as they were treated seriously by most contemporaries

I’d go even further and say that applies more generally to life, and it’s hard to tell beforehand. Life is about the narratives we tell ourselves and others. If you have a grand vision and it works, you’re praised as a visionary with a reality distortion field. If it fails, people mock you.

Some of the seemingly preposterous small projects of the South Sea Bubble are not all that farcical when considered in the context of that era. Alchemy was still being taken seriously […] perpetual motion was far more respectable then […] Thus simply looking at the stated aims of various bubbles from 1720 is rather misleading. And the vast majority of the projects were for relatively mundane businesses

This is also a good point. Knowing what we know now, it’s easy to say a 1700 venture to turn lead into gold is worthless. Will people in three centuries say the same thing about our attempts to make a virtual metaverse? I think the only thing I can be sure of regarding the future is that it’ll be crazier than I can imagine.

while bubbles have a very negative image, they have made positive contributions to society, by spurring development of new technologies and new business models

I’ve read that the internet bubble allowed for cable networks to be built, laying the foundations for our networks today. Business models that were too early for their time or badly leveraged also keep resurfacing, and sometimes they actually work this time round.

can we use history to help develop guidelines for detecting dangerous bubbles? The task is certainly not easy, and it seems unlikely that a foolproof method can be found. But one approach […] is to try to develop a gullibility index

Another might be the expectations of profits that passive corporate investments can achieve, which tend to soar during bubbles

Yet another might be derived from the nature of the new projects being offered to the public

Andrew concludes by suggesting ways to measure a bubble, which is still something the broader community has not solved today. People buying Tilray on the rise were convinced it wasn’t a bubble, and I’m sure that’s happening to any number of things today. He details more in his other paper here; perhaps these could be first steps in measuring bubbles better.

Footnotes

- J. Oldmixon, The History of England: During the Reigns of King William and Queen Mary, Queen Anne, King George I. Being the Sequel of the Reigns of the Stuarts, T.Cox, 1735

- “The man of genius who essayed this bold and successful inroad upon public credulity, merely stated in his prospectus that the required capital was half a million, in five thousand shares of [£100] each, deposit [£2] per share. Each subscriber, paying his deposit, would be entitled to [£100] per annum per share. How this immense profit was to be obtained, he did not condescend to inform them at that time, but promised, that in a month full particulars should be duly announced, and a call made for the remaining [£98] of the subscription. Next morning, at nine o’clock, this great man opened an office in Cornhill. Crowds of people beset his door, and when he shut up at three o’clock, he found that no less than one thousand shares had been subscribed for, and the deposits paid. He was thus, in five hours, the winner of [£2,000]. He was philosopher enough to be contented with his venture, and set off the same evening for the Continent. He was never heard of again”

- “Starting on Friday, 18 December 1719, the Daily Post carried for several days an ad for an “extraordinary scheme for a new insurance company to be proposed, (whereof publick notice will speedily be given in this paper),” with “permits to subscribe” offered for £0.05 each. No names of projectors, nor details of the scheme were cited. The sale of the “permits” took place on Thursday, 24 December. Two days later, this same paper had an ad which offered refunds for the “several hundred” of those permits that had been sold, and explained that the whole thing was a hoax designed to show how easy it was to “impose upon a credulous multitude.” The ad mentioned that the person who had collected the money was unknown to anyone in the crowd, and signed receipts with a name made up from the initials of the 6 people who concocted the scheme”

If you liked this, sign up for my monthly finance and tech newsletter: